This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

Jellyfish Dreams

In the past I’ve made a praise of corsets, but now I want to embrace the opposite impulse, towards formlessness. Since I was a child, I’ve had a fascination with jellyfish, the strange way their bell-shaped bodies expand and contract, pulsing with a curious energy, transparent, trailing the tendrils and ribbons of their languid arms. How calm they are, how serene. To let the light pass through, to drift, to “float forever in a moon-green pool,” to be washed continually in the salt brine of the sea, to live forever or a single day, to bloom in phosphorescent bulbs in the weird and dark reaches of a sublunar liquid, eating up in the bell of my body innumerable small fish, diatoms, protazoans, little crustaceans, floating white specks of plankton—somehow it all seems so lovely, to let go like that and become as diaphanous as a piece of chiffon. After all, I’ve always found a kind of release in swimming, a suspension of time and space and world.

But on closer examination, there is something about formlessness that actually requires more effort. Form is a given; structures surround us and compel us. Obligations press into us, conventions, hierarchies, all these rigid, ossifying things. The world gets filtered through, then, and we miss so much, simply because we fail to be open. If we allowed ourselves to linger a little more, if we allowed ourselves a kind of transparency, maybe something would come up from the seafloor of ourselves and find itself at last shining in the light of the sun, struck by a golden shard or splinter.

Now that I consider them more closely, it seems that jellyfish might be sea-ghosts and that perhaps when we are dead our souls become like this. Floating and amorphous, pulsating with light and motion and yet adrift, soft and yet able to paralyze—might this be the natural state of the soul as it drifts through the great darkness of that other world? Are we like this even now, when we sit down with ourselves—amorphous beings sailing through an infinite void, trailing rags of glory?

Let us not lose our languidness; even if we are trapped in form, let us exchange that form a hundred times over, modify it, chip little pieces off of it bit by bit. When I longed for the strictures of the corset, it was because I had the energy to resist my real nature, which is, in the final analysis, something more akin to the reflection of a moonbeam on a sliver of water. Let us melt and change, then, and shift and be endlessly Protean. I grow weary of the world, and I have spent too long trying to fish myself out of the tidepool of dreams. Why should I not accede, why should I not allow myself to drift there and be carried, little by little, into the vaster deeps of the sea? Something will lull me asleep there, slippery and lubricious and utterly without edges.

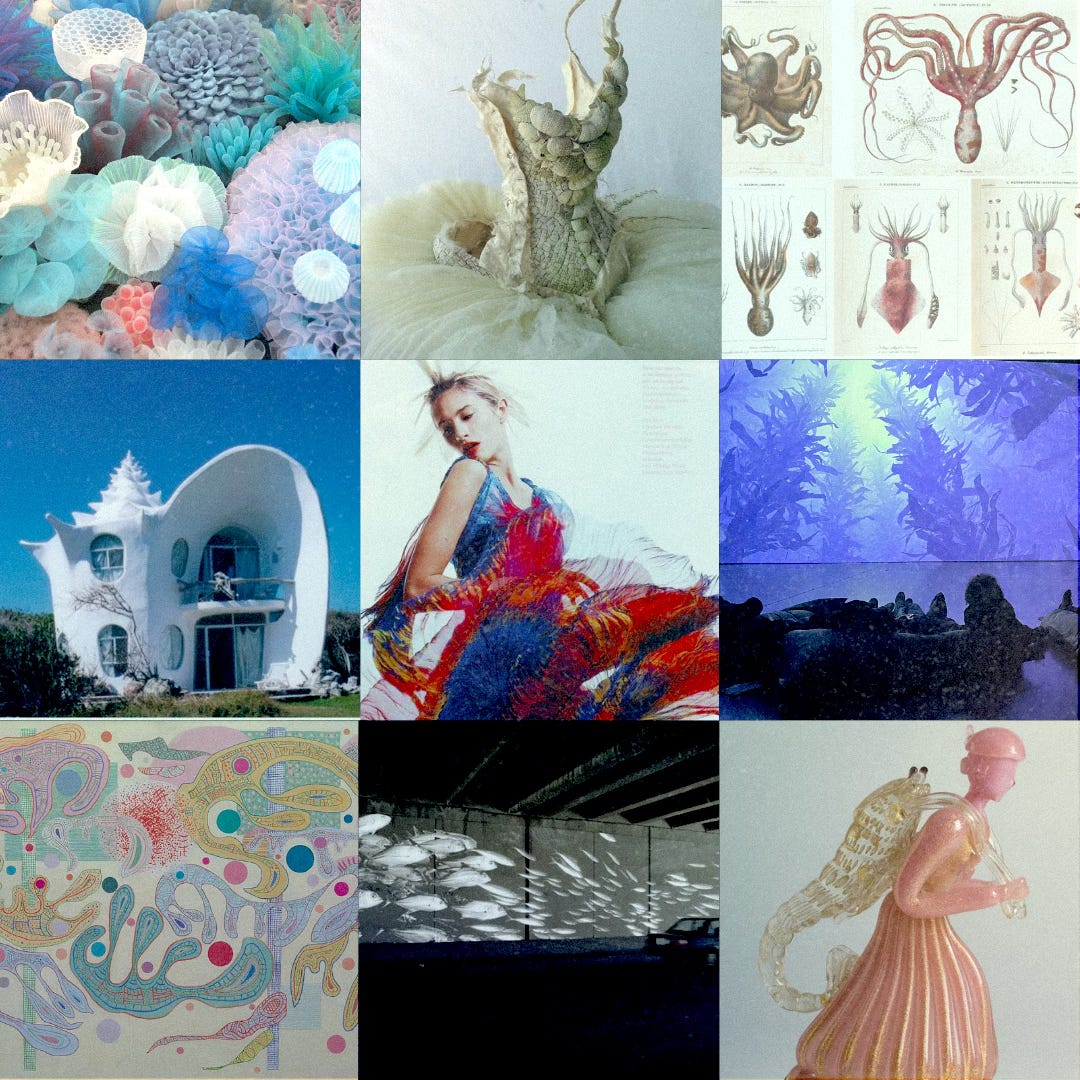

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Mariko Kusumoto, “Seabed” (2023): Mariko Kusumoto creates work in fiber and metal, and her seascapes are shimmering, gauzy collections of multicolored coral. In an interview, she stated, “A playful, happy atmosphere pervades my work. I always like to leave some space for the viewer’s imagination: I hope the viewer experiences discovery, surprise, and wonder through my work.”

textile pieces by Mariko Kusumoto “Sea Urchin Tutu” by Catherine Latson from The Garment Series (2012-16): Sculptor Catherine Latson is interested in “the macro- and microstructures of living organisms,” and in her Garments series, she uses the materials of the natural world to fabricate couture-esque gowns of marigold, wedding dresses of tapioca root, corsets of birch bark, all singularly strange and arresting and beautiful. This little sea urchin number uses sea urchin shells layered onto an old Victorian bodice, tutu’d by layers of frothy tulle. Its marine inspiration and organic off-white remind me of Alexander McQueen’s oyster dress.

Sea Urchin Tutu by Catherine Latson Cephalopods illustrations by Jean-Baptiste Vérany (1851): In 1822, Jean-Baptiste Vérany (1800–1865) abandoned his career plan of taking over his father’s pharmacy, instead choosing to assist zoologist Franco Bonelli. Over the following decades, he would develop a specialty in cephalopods, discovering new species and producing intensely detailed illustrations of these strange molluscan creatures. A few weeks ago, I went to see the Blaschka glass flowers at Harvard, and it turns out that the Blaschkas’ sketches for their models of cephalopods were highly inspired by Vérany’s drawings.

The Shell House in Isla Mujeres, Mexico: If you’ve ever wanted to live in a conch shell, the Shell House currently operates as an Airbnb known to locals as Casa Caracol. The legend goes that one day, as they were both out at sea fishing, a fisherman of the nearby Isla Holbox got into a dispute with a fisherman of Isla Mujeres. The fisherman from Isla Holbox boasted that he had the biggest fish in the world. Well, countered the fisherman from Isla Mujeres, I have the biggest seashell in the world. Apparently, the shell contained enough conch meat to feed everyone on the island, so they all made ceviche and everyone was happy. The real story behind Casa Caracol is less fanciful—but no less fascinating. In 1967, architect Eduardo Ocampo came to Isla Mujeres to work on a hotel and settled there with his wife. Frequently visited by his brother Octavio, a painter, Eduardo wanted to build him an art studio and took inspiration from the many seashells that clustered along the island’s shoreline. Construction began in 2001 and took three years to complete. Eduardo often needed to build many aspects of the home by himself, as certain elements, like the conch’s spiral peak, were difficult for the workers to even envision. Every wall of the house is rounded, and shell-encrusted mirrors and Octavio’s paintings of mermaids bring a touch of color to the pristine white interiors.

from Casa Caracol's Airbnb page Sara Ziff in Alexander McQueen S/S 2003 by John Scarisbrick for Vogue Russia, April 2003, “Vivid Colours of Spring”: For his Spring 2003 collection, McQueen took inspiration from an earlier era of seafaring, concocting a narrative of shipwrecks and pirates and oysters, conquistadors losing themselves in the rainbow bewilderment of an Amazonian rainforest. Here, the way that blue and red chiffon of the dress comes up in gauzy layers puts me in mind of a jellyfish or the transparent, ruffled fin of a fish.

colorful dresses from Alexander McQueen Spring 2003 Wu Tsang, Of Whales at the ICA Boston (2024): Wu Tsang (1982–) was inspired by Melville’s Moby Dick to create a trilogy of films and video installations, of which Of Whales is the second part. Tsang created the video on the Unity gaming platform, employing XR (extended reality) technology in order to capture a whale’s experience of sounding the ocean depths. Ribbons of light break apart, stir, quiver; jellyfish bob and float; a whale’s tail makes its way through pinpricks of light. Lying there on the beanbag chairs in front of that vast oceanscape screen, I could lose myself easily, drift off to the rhythms of the sea. Of Whales was particularly apt at the ICA, which is located by the Boston Harbor—New England in the 19th century was a prime whaling hub, and the Pequod in Moby Dick, after all, departs from Nantucket.

Vasily Kandinsky, Capricious Forms (1937): I once had to do a report on Kandinsky for 8th grade English class—we all chose an artist to research, and I landed on Kandinsky, happy to while away time in the library flipping through large reproductions of his colorful rhapsodies of shape and form. Capricious Forms comes from his final period as an artist, in which he synthesized the different elements of his earlier periods. Here, aside from the perfect rounded orbs of the circles and the few squares and rectangles that recede into the background, the shapes are asymmetrical, strange, motile, and fluid. They resemble scientific drawings—tissue seen under a microscope, the teeming and capricious world of biology, something living and growing and always in play.

Reflective paint mural in I-95 underpass on Columbia Avenue in Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood: Fishtown deserved an appropriately fishy mural, but who would have predicted one this beautiful, swarming with a school of gleaming, silver fish? It seems to make you want to question reality for a brief moment, to wonder if you’re in some aquatic dream, to pinch yourself and ask, Am I in an underpass? Or am I underwater?

Ercole Barovier, Woman With Shrimp, 1930s: It was on Murano, the little glassmaking island off of Venice, that Ercole Barovier was born in 1889, it was on Murano that Ercole Barovier died in 1974, and it was on Murano that he learned, refined, and practiced the craft that defined the island’s primary export. Why is this shrimp-colored woman carrying an oversized, transparent specimen of that crustacean on her back, holding its creepy shrimpy arms in her two hands like a schoolgirl clutching the straps of her backpack—or as though girl and shrimp are inseparable besties? Perhaps they are—and who am I to judge?

3 Things I’m in Love With This Week

The home of former British Vogue fashion director Lucinda Chambers: Chambers’ proclivity for bold prints, zany patterns, and eclectic items seemingly slapdashed together (but always with a method to the madness) is not limited to the demesne of fashion. It translates—thrillingly, beautifully—to the world of interiors, where rooms are painted bright yellow and bright red, floral fabrics wrestle with stripes, and a motley collection of plates adorn a wall above the bathtub, just in case you needed to eat while soaking. I also love her Easter tablescape, which seems like it would give you a headache but comes together in a way that is bizarrely, humorously harmonious.

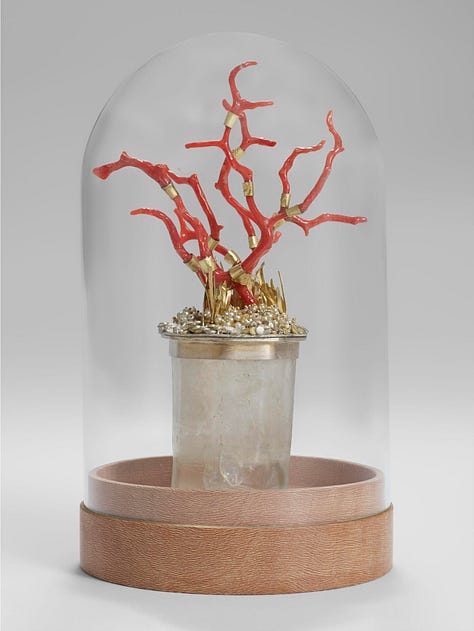

Lucinda Chambers' home, shot by Owen Gale for House & Garden “Unboxing REAL shipwrecked treasure and ancient archeological jewellery” video by the Victoria and Albert Museum: A 17th-century Peruvian solid gold chalice, a contemporary coral, gold, and pearl work grafted onto sand-encrusted Tudor glass, a pair of gold Roman Empire serpent armlets, a carnelian and blue enameled comb worn by Empress Josephine—curator Sophie Morris reveals the secrets of these shipwrecked treasures (and more!), carefully piecing together each item’s history and context. Dead men tell no tales, but objects never die.

Romilly Saumarez Smith, Tudor Glass with Coral Reef (2016) / Ruth Tomlinson, Time Capsule (2021) / gold Roman armlet Review of the restaurant 66 by A.A. Gill for Vanity Fair, seen in Graydon Carter’s When the Going was Good: Like every other young writer, I was shockèd by the sheer numbers in Bryan Burrough’s review of former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter’s memoir: a writer for VF during the Carter era, at his peak Burroughs was paid $498,141 to produce a measly three articles a year, usually around 10,000 words each. In other words, oh boy was the going good. Expensed breakfasts, catered dinners at one’s home, town cars, interest-free loans to buy new homes, an “eyebrow lady” on standby—one thinks of the perks of today’s Big Tech workers, all those little nerds with their on-site masseuses, ski trips, and raspberry yogurt-covered pretzels.1 Follow the advertising, as they say.

Anyway, Burrough’s article spurred me to read Carter’s memoir, which was, on the whole, lackluster, dull, skimmable, and—dare I say it?—Canadian. What drives Carter’s ethos as a magazine editor? What pushed him to strive to reach the top of that ladder? What valuable life advice does he have that isn’t trite or cliché? And—barring all that—what really juicy celebrity gossip? The most riveting part of the book for me was when he quoted an excerpt from one of A.A. Gill’s restaurant reviews (and perhaps that is the secret, that a good editor knows how to spot the good writers and give them the spotlight). Gill is a great writer. Literary history may not remember the dailies, the weeklies, the monthlies the way we remember Ulysses or “The Waste Land.” But when magazine writing hits, it hits. Where in fiction can we find something to match the savagery, the sadistic pleasure of the bad review? Where else are we to find gems like: “The lighting is nighty-night nursery dim, as if keeping it crepuscular will stop you from noticing that it looks like every crêperie in Berlin, and that the babe in the corner isn’t Claudia Schiffer but a Serb television producer on steroids” and “How clever are shrimp-and-foie-gras dumplings with grapefruit dipping sauce? What if we called them fishy liver-filled condoms. They were properly vile, with a savor that lingered like a lovelorn drunk and tasted as if your mouth had been used as the swab bin in an animal hospital”?

Words of Wisdom

The ability to feel mixed emotions is a sign of maturity. If people can blend contradictory emotions together, such as happiness with guilt, or anger with love, it shows that they can encompass life’s emotional complexity. Experienced together, opposing feelings tame each other. Once people develop the ability to feel different emotions at the same time, the world ripens into something richer and deeper. Instead of having a single, intense, one-dimensional emotional reaction, they can experience several different feelings that reflect the nuances of the situation, However, the reactions of emotionally immature people tend to be black-and-white, with no gray areas. This rules out ambivalence, dilemmas, and other emotionally complicated experiences.

—Lindsay C. Gibson, Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents

Poetry Corner

This post was inspired by four poems:

Marianne Moore wrote an early version of “The Jellyfish” in 20 very short lines, then later revised it into eight longer lines, cutting out the ending and highlighting the rhymes between the second and fourth lines (“charm” / “arm”) and the sixth and eighth lines (“meant” / “intent”). Pairs of opposites (“Visible, invisible,” “it opens / and it closes”) embody the jellyfish’s “fluctuating charm,” the elusive rhythms of its shape-shifting. The precise language of “amber-tinctured amethyst” is echoed in a later poem of hers, and one of my favorite poems, “The Fish,” where an “ink-/bespattered jelly fish” is only one creature among many: “crabs like green / lilies,” “submarine / toadstools,” “crow-blue mussel-shells,” “barnacles.” Moore approaches her subject with scientific precision and detachment, a precision brought out by the rigors of her form (1 syllable, then 3, then 9, then 6, then 8, in an AABBC rhyme scheme)—a highly, visibly artificial form whose fluctuating line lengths compel Moore to cleave the word “ac- / cident” by a line break and rhyme “ac-” with “lack,” making us hyper-alert to language, to its arbitrariness out of which we nevertheless make meaning. The poem then moves from precise imagery of the sea and its creatures to an ecological interest in the human-caused “marks of abuse” present on the cliffside. Nothing can erase these marks; the sea cannot “revive / its youth.” Nevertheless, it’s alive, it teems with the life that occupies the first five stanzas, and thus “grows old in it”—as do we all, carrying such marks of time and yet “defiant.”

Sylvia Plath’s “Aquatic Nocturne,” all free verse and lowercase and barely punctuated, captures something of the same precision of imagery, though almost with the eye of the dreamer rather than the scientist. Liquid L sounds abound—“dilute light,” “tilting silver,” “flicker gilt”—giving us a feeling of being underwater, in a strange sublunar world where strange creatures glimmer and gleam, “shrewd” and “elusive,” “lithe” and “agile.” “Water’s Lubricious Edges,” a poem I only discovered about a month ago or so, evokes a similar feeling but combines it with an eroticism—“paps of pleasure,” “lascivious luminescence”—and hypnotizing repetition that breaks and flows and rejoins as water itself does.

Beauty Tip

Make a gratitude tree! I came across this idea in a video by Audrey of French Countryside Diary: with her wicker basket-equipped bicycle, she journeys into the springtime beauty of her surrounding French countryside and culls a few pretty branches that spring has adorned with little green leaves and nascent blossoms. At home she arranges them artfully in a(nother, larger) wicker basket, writes out a few things she’s grateful for on little white tags, and festoons the branches with the tags and bits of hanging ribbon. The idea is for visitors passing through the house to write up their own tags, adding to the goodwill and generosity that are the nutritive soil in which this “tree” thrives.

Lingering Question

Would you rather have a shrimp backpack, a sea urchin tutu, or a seashell house? I would personally live in the seashell house… I wonder if it’d make the sound of the sea, if you’d hear a gentle murmur of waves at all times, the soft fall and swell, sometimes roaring to a mighty crash.

Dear Readers, it is spring here and the flowers are blooming and everything is beautiful. I hope you have a lovely, lovely weekend—even better if it involves pastry of some kind. Yesterday I baked a mixed berry galette. Anyway, as always, let me know what you think in the comments, like this post if you appreciate the puns, and share with a friend! <3

My friend at Google took me to their office once and I had the best raspberry yogurt covered pretzels that I haven’t been able to find since.

In your meditation on corsets and jellyfish, you consider two wildly different modes of being, both of which provide value. And you do this with the most tantalizing of language. Wonderful as always, Ramya! 👏

"To be washed continually in the salt brine of the sea, to live forever or a single day, to bloom in phosphorescent bulbs in the weird and dark reaches of a sublunar liquid, eating up in the bell of my body innumerable small fish, diatoms, protazoans, little crustaceans, floating white specks of plankton—somehow it all seems so lovely, to let go like that and become as diaphanous as a piece of chiffon."