Gratitude and Greed

Having and wanting, satisfaction and striving, acceptance and ambition—is there ever a happy middle?

Gratitude is the obvious virtue. Indeed, there is so much to be grateful for, one doesn’t know quite where to start. Personally, I am grateful for my mother and father (I heartily shake hands with them for having produced such a masterpiece as myself, and thankfully none other), for flowers, clouds, jewelry, sundresses, for floral anything, for “pearls, harmonicas, jujubes, aspirins!”1 for Shakespeare and Keats, the Brontë sisters and Virginia Woolf, for lazy sunless mornings in bed, for new books and old bookshops, for sparkly liquid eyeshadow, for oranges that can be peeled so as to facilitate offering the segments, fresh, citrus-smelling, trailing wisps of white, to a loved one, for the million beautiful coruscations, bendings, and ripples of light, for all those summer afternoons I spent lying down, listening to Arvo Pärt, watching the trees laden with leaves sway like a sea heaving, for summer storms, for orchids, tea, balloons, and swans, for my taste in movies, which was given to me by my father, for my taste in clothes, which was given to me by my mother, for snow and my childhood memories of it, for museums, libraries, cafés, and parks, for people who pick up after their dogs, for my friends, for men, for pretty stationery, for fountain pens, for rocking chairs, and for you, dear reader.

Greed, I think, as a virtue is only celebrated in certain circles, by those of an acquisitive nature. The dollar signs flash in their beady, money-grubbing eyes, they hear the cha-ching of the cash register, they see the numbers rising upwards and forever, and they are smitten. More is more for them, splendor and grandeur are their birthright. And yet I too, when I peer down the mineshaft of my soul and dare to shine a lamp into its darker corners (bats flap out, spiders scuttle forth), see that I am not entirely devoid of this impulse. One has a beautiful dress, and yet one could always have another; one has had the opportunity to learn the violin, and yet one has always wanted to learn the harp; one has five hundred readers, and yet one could always have five thousand.

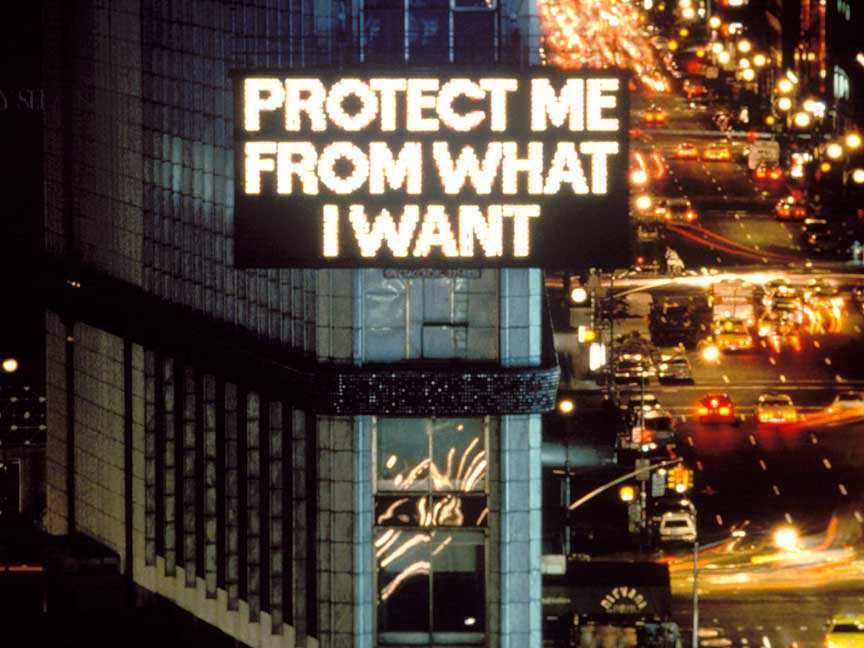

Desire, the religions and philosophers tell us, is bad. Wanting is lack, wanting is void—why hollow yourself out like that? Why drain yourself of everything that could fill you? Whatever the material conditions of your life, whatever the outward circumstances, whatever the misfortunes and blows, the capricious pummelings of fate, there is always a grain of gold among the specks of dust, something perfect and flawless among all that rubble. Hold it to the light, turn it around in your fingers, clutch it to your chest, keep it in the little treasure box of your heart, where you may, from time to time, crack open the lid, gaze fondly upon it, and feel yourself immensely, immeasurably full.

But isn’t ambition nothing more than this wanting more? And who has ever achieved anything without wanting more than what one already has? If one were satisfied with little huts built of sticks, one wouldn’t have Versailles or the Taj Mahal; if one were satisfied with horses and donkeys and rowboats and bullock carts, one wouldn’t have cars and planes and trains and steamships; if one were satisfied with the oral tradition and the deplorable burden of keeping everything inside of one’s head, overstuffing it with receipts, bills, lists, names, numbers, faces, facts, recipes, stray fragments of poetry, tales long and short, like a drawer fit to burst with papers, one would not have the pleasure of reading, nor the relief of writing. If we have crawled out of our primordial slime into the light of God, it is only because we have craned our necks, lifted our gazes, and looked upwards.

Literature, however, is filled with dire warnings about this upward looking. Icarus, we remember, perished for soaring too close to the sun, the wax melting, the wings failing, the boy toppling headlong into the sea. Phaeton sought to drive his father Apollo’s sun chariot but, no god himself, burned cities and boiled seas and had to be put to death. Arachne challenged Athena to a weaving contest and was humbled into a spider.

Think, too, of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, whose titular heroine, Emma Bovary, dreams for higher than what she has and dies for it. The narrowness of her provincial life pinches her. As a girl, she surfeits herself on religious visions and cheap romance novels, saints and sentiment. Her diet—one of bonbons, cream puffs, spun pink sugar—could not allow her to stomach the slightly stale bread of reality, to chew its hard crust, swallow down the bland mouthful. Marriage, to a country doctor, turns out to contain no luxuries, no “romance”—“the words ‘bliss,’ ‘passion,’ and ‘intoxication,’ which had seemed so beautiful to her in books,” turn up their noses at reality, skulk at the doorway, and refuse to cross the threshold from fiction to fact.2

One day she goes to a ball and snatches a wisp of this dream-life: the rich, the beautiful, the dashing, all gilded and burnished and so bright she can see her own reflection in the polished surface of their world. It does not occur to her that life is not all roses and swans and perfumed moonlight for these people, that they, too, feel a little pinched by life here, prodded by fate there. She is one of those women who, if she must cry, would rather cry under velvet coverlets, propped up on swansdown pillows, wearing a silk nightgown, in a room with delicate wallpaper and a cut glass chandelier and bunches of flowers, freshly picked from the garden, arranged in porcelain vases, a lady’s maid bringing her a lace handkerchief on a silver salver.

She founders her marriage—whatever could be good and happy and salvageable in it—on the shoals of adultery. She subscribes to women’s magazines and learns the latest fashions, keeps up with Parisian “first nights, horse races, and soirées,” as if preparing herself for the day when the portal of her fantasies will open at last, beckoning her to step in and plug that knowledge into its proper use. She lies to her husband, she ignores her daughter. She decorates her life with the props of these fantasies and runs up ruinous debts.

About 70 years later, and on the male side, it does not fare much better. James Gatz, born to penniless farmers in rural North Dakota, through luck and hard work and his own brains, cobbles the project of himself into “the Great” Gatsby, aspiring to that high heaven in which his love Daisy Buchanan floats. Yet he, too, dies for his dream; the green light winks forever across the bay, forever out of reach, inaccessible, unpossessable.

If these two had practiced gratitude, as popular philosophers and armchair psychologists exhort us, they would have been happy, they would not have been ruined. After all, a humble hut has its own beauty, quite distinct from Versailles and the Taj Mahal; horses and donkeys have an animal charm cars do not; with the invention of writing our memories atrophied. The brightness of every gain is pursued by the shadow of loss. In Madame Bovary, Flaubert notices what his heroine does not, that her provincial country life is imbued with its own beauty—“The evening mist was passing among the leafless poplars, softening their outlines with a tinge of violet, paler and more transparent than fine gauze caught in their branches”—that her dull, unsparkling husband nevertheless loves her earnestly and strives for her happiness.3

We may chalk up the failures of Emma and Gatsby to their epochs and circumstances—today, we may say to ourselves, society is less rigid, anyone who strives and wishes to succeed, who hews to the path of one’s dream, is liable to get somewhere. To want more than one has—maybe not materially, maybe in love, in achievement, in skill—isn’t this what attaches us to the world and gives life its animating vigor? What can be more admirable than to not only dream but to put force and muscle behind dragging that dream into life itself? And yet, chasing chimeras, dashing after will-o’-the-wisps, our brains fogged, our sight clouded, aren’t we most in danger of tripping over our own feet and falling on our faces?

I wonder if there is, as Aristotle argues of virtue, a proper and happy mean between acceptance and ambition. Can it be possible to have and to want, to be satisfied and yet still to strive? Or is one condemned to vaulting hopelessly from one pole to the other, moving so rapidly between them that, practically, it at least looks and feels and seems that one has reached this happy mean, when there is only endless oscillation?

For reasons not entirely within my control, for the past few years my life seemed to have stalled around me like dirty bathwater. I felt terribly behind, constrained, stuck, my wings clipped, my desires winking at me not just from across a bay but across whole leagues of ocean. I broke down, I wept bitterly. Why had X happened, why had Y happened, most of all, why had they happened to me? Then a better conscience than my own reproached me gently. “Don’t you think you have a lot to be thankful for?” And indeed, reader, I did.

The list includes all I have enumerated above, plus a thousand others I think it safer to keep between myself and God. The list is infinite; something new is added to it each and every day. My life was not on pause, I was not living an intermission, there is no waiting room when it comes to the glory and the din of life. This, too, was my life; this, too, was the rage and the swell and the fury of the sea—if I saw myself as forever standing on the shore, I could not swim across the bay or across however many thousands of leagues that lay between myself and my incorruptible vision.

A man who cannot appreciate a cottage does not deserve a skyscraper. Perhaps acceptance is the only solid foundation on which ambition can be built. Perhaps the fulfillment of all we desire already lies within our lives, seeds hidden in impoverished soil, which only need to be found out, and delighted at, and cared for, and nourished, and watered, and loved.

If you’ve reached the bottom of this page, thank you so much for reading! It really means a lot to me. <3 If you enjoyed, please give this post a like, and I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments—what are some things you’re grateful for in your life right now?

Also you may notice that I’ve changed the “logo” of Soul-Making and have put this poor newsletter through a sort of semi-rebranding. This is mainly because I get bored easizly—but let me know what you think! And to everyone who celebrates, I hope you have a lovely Thanksgiving!

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary, translated by Lydia Davis.

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary, translated by Lydia Davis.

Where I live now there is no Thanksgiving Day but I grew up in that world & remember some things fondly, including Mrs. Wertheimer’s roast goose once and my father’s Thompson Turkey dinners many times. But today, where it is now 28 Nov, I am most grateful for something else. My haphazard non-linear life somehow handed me a way at age 70 to help a number of younger people have much better lives than they had before or maybe even thought possible before. Today, they are healthier & better educated & safer than otherwise. That alone has made the ten years since the most meaningful of a life otherwise notable primarily for its unrealized potential. So today, I don’t need a turkey dinner. I am already thankful.

Beautiful work as always, Ramya. In counting things to be grateful for today - reading your words will be very high on my list.

And also, I definitely do think there can be a happy middle with Gratitude and Ambition.

Personally, I like to think of this with a comparison to the pursuit of beauty too - because obviously, beauty in this life never comes in only a single shade.

In fact, we can actually understand beauty best when we start to realise how it can be found in endless variations (i.e everything from nature, to art, to buildings, to people, starlight, sunsets and so on).

So, to some extent, I think it's the same with gratitude too.

Pursuing more does not necessarily mean we become any less grateful for what we have already - it is just part of our process of exploring how many ways we can experience this feeling.