This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

A Love Letter to the Love Letter

I love to write love letters, and I love to read love letters. One should have passionate love affairs for the sole purpose of writing love letters. Indeed, what is the point of having a lover, if not as a recipient for the bottled-up billets-doux, the millions of unsent missives that perch on the branches of one’s heart, their wings aching to take off into that rarefied atmosphere where everything is bathed in an aroma of roses and the clouds are always tinged with a blush of pink? One has all of this pent-up emotion, one has all of this passion, one has all this desperate fire inside of oneself, one wants to write, sing, shout, dance upon an empty stage, but like the speaker of Shelley’s “Question,” who plucks imaginary flowers from an imaginary garden in an imaginary Spring that he might present it—“Oh! to whom?”

The love letter is a Janus-faced thing: on the one hand, it signifies authenticity, earnestness, purity, veracity, the soul laid bare, pouring itself in an outflow of passion and emotion, hardly able to contain itself. The handwritten letter especially documents the speed of hand and thought (“This living hand, now warm and capable”), the paroxysms of the heart as it is caught up in now this stream of feeling, now that one, for handwriting is as peculiar to a person as his or her face, as intimate as a kiss. Within the secret folds of the letter, one can say things to the beloved one would blush and stammer to say face-to-face; one can truly be oneself behind this unassuming mask of paper. And yet on the other hand it is a mask: a creation, a fabrication, a fiction. A love letter can be artificial, formulaic, trite—it can borrow from the standard lover’s stock of words and phrases, simply a reformulation of so many secondhand sentiments, gleaned unconsciously from books and movies and plays and poems. Coming from the mind, a product of the intellect, it can flatter its way into affections, strategize its way past the defenses of the heart, battering down, word by word, the ramparts and barricades, a finely-tuned weapon of amorous battle.

In the Ars Amatoria, Ovid instructs women in the art of writing letters on wax tablets. He tells them to avoid waxing poetic, however: “Make him fear and hope together, every time you write, / let hope seem more certain and fear grow less. / Write elegantly, girls, but in neutral ordinary words, / an everyday sort of style pleases.” So, too, does Richard Steele warn men from following the example of “Colonel Constant”; instead, they should model themselves after “John Careless.” While both men write from the front lines of war, Constant makes promises of his “Place” in the lady’s “Esteem,” implores her to keep him in her memory, tells her of his “Tears.” Careless, on the other hand, makes light of the dangers of battle and light of his passion for the lady. “The pleasant Man she will desire for her own Sake; but the languishing Lover has nothing to hope from but her pity” is the sage conclusion Steele draws. Nevertheless, my own heart goes out to the languishing Lover. Silly he may be, ridiculous he may be, but that he bleeds onto the page is only a sign of a heart that is able to be pierced—that is to say, a heart that feels.

Mood Board of the Week

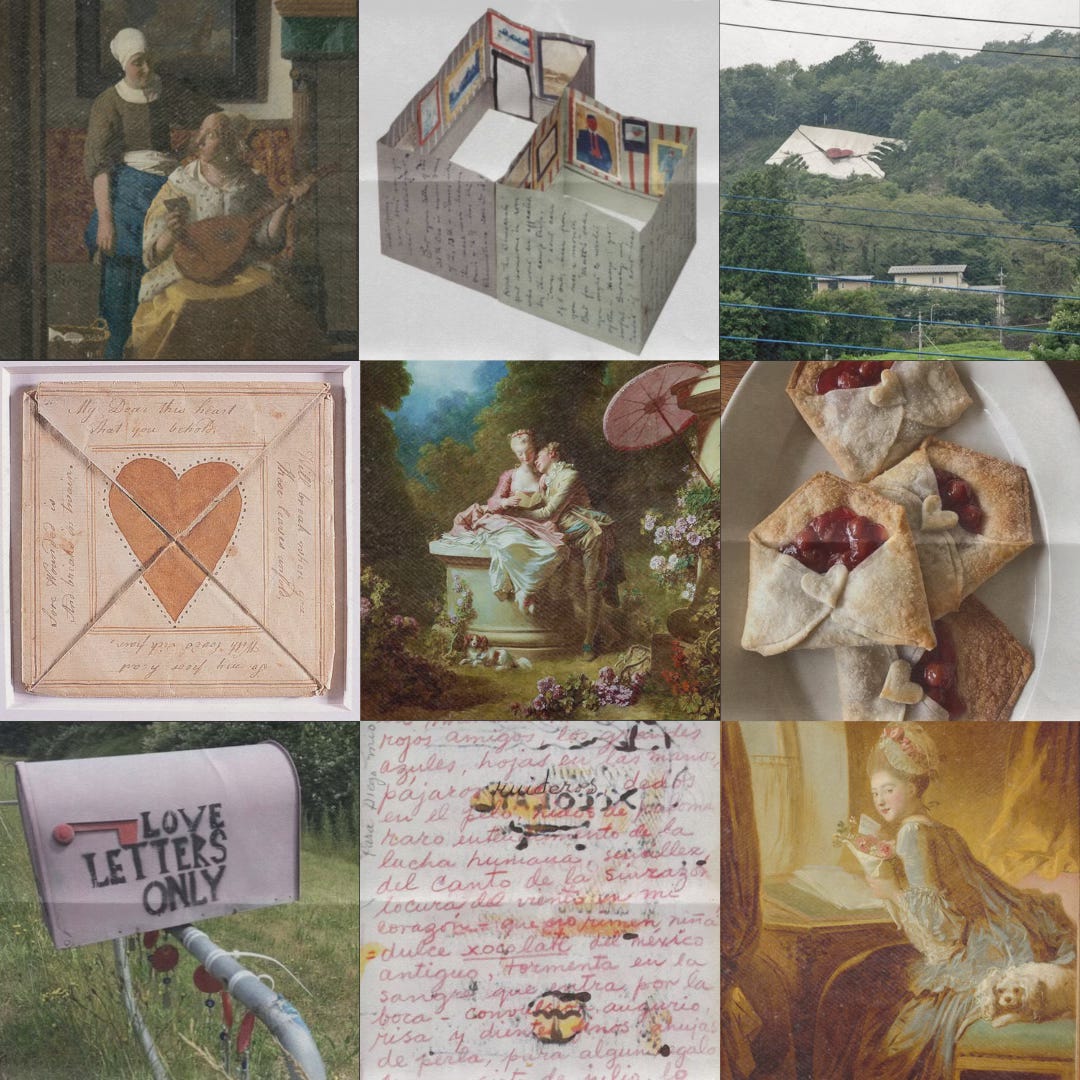

(left to right, top to bottom)

Jan Vermeer, The Love Letter (1669-70): This painting depicts a woman holding a cittern in one hand (a stringed instrument similar to a 12-string guitar), a letter in the other, as she looks towards her maid who stands behind her. The theme of maid and mistress was common in Dutch genre painting of the time, and here the shared glance between the two, the maid wearing an almost wry smile, the mistress looking up to her as if for guidance, upends the traditional social hierarchy, showing a close emotional connection. The way that the two figures are placed at a distance from the viewer, tucked into a dark interior, with a wall and a curtain in the foreground, creates a sense of intimacy—we feel that we are peering into an intensely private scene. The broom and the fact that the lady has her slippers off contain sexual undertones, while music-making traditionally symbolized love.

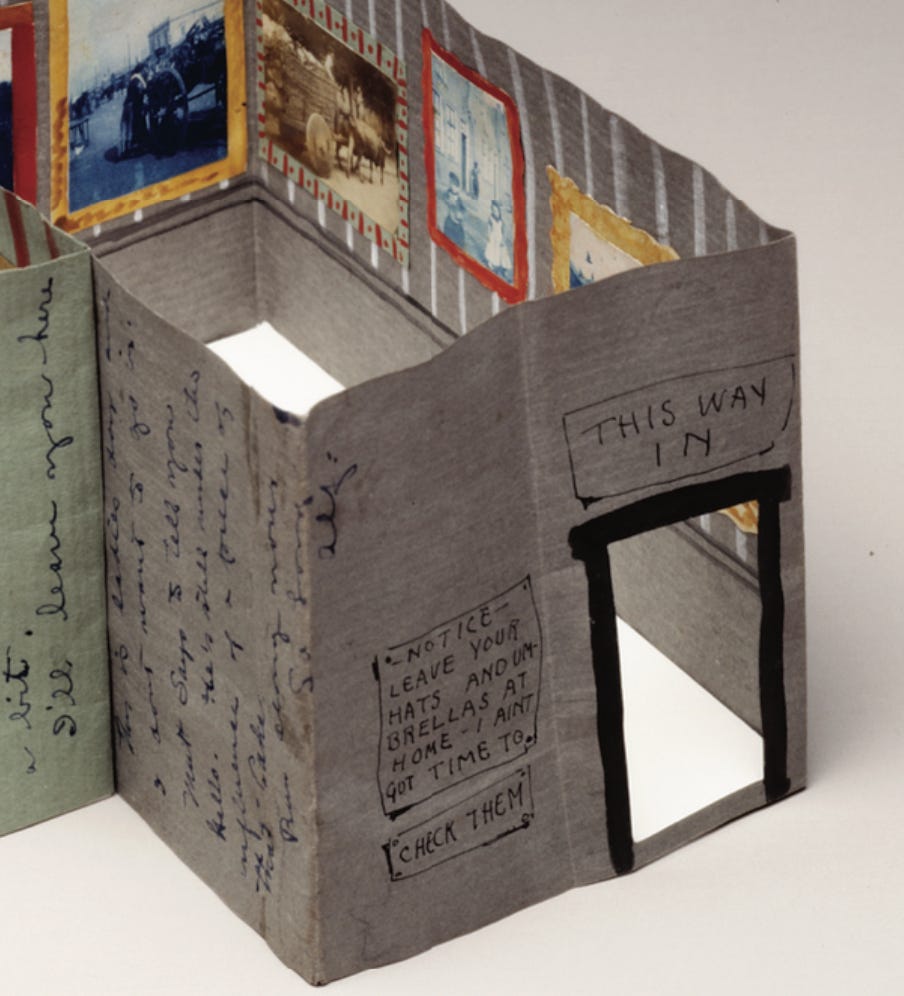

Alfred Joseph Frueh, Letter to Giuliette Fanciulli, 1913: American caricaturist and cartoonist Alfred Joseph Frueh met his wife Giuliette Fanciulli while traveling abroad between 1910 and 1914. In 1913, when she was still just his fiancée, he wrote her this love letter that expands out to form a miniature art gallery in order to prepare her for the “GALLERY MARATHON” that she would experience in Paris. At the front entrance of this little paper gallery is a sign that reads, “—NOTICE—LEAVE YOUR HATS AND UM-BRELLAS AT HOME—I AIN’T GOT TIME TO CHECK THEM.”

Masayuki Takahashi, Love Letter (1989): Fujino is a small town that serves as a popular day trip from Tokyo, and in 1989, Masayuki Takahashi created a giant love letter, 17 meters high and 26 meters wide, sealed with a perfect red heart, and planted it into the lush mountains, where it looks like it’s being held by two green hands. Over time, the piece started to decay and disintegrate, but Takahashi noted that the Fujino community, which is home to several art galleries and studios, has grown to care more about the environment and the area: “When my artwork needs maintenance, people notice and volunteer their time to help me repair.”1

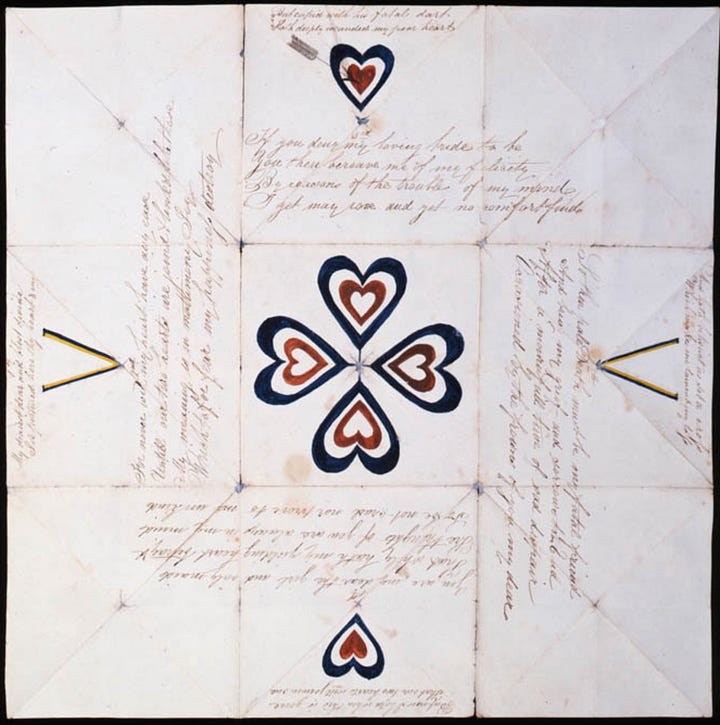

Artist unidentified, Love Token for Sarah Newlin, Pennsylvania, 1799: I love this adorable letter, which is currently in the collection of the American Folk Art Museum. Valentines made their appearance in America when Pennsylvania Germans in the mid-18th century brought over the tradition of sending love tokens to lovers and friends. Handmade Valentines of the time often featured decorative borders, lacelike cutwork, and drawings of hearts, flowers, lovebirds, lover’s knots, and labyrinths, symbols of the letters’ own intricacy. Puzzle purses—letters that were ornately decorated and then folded, almost origami-like, so that unfolding the different parts would reveal new pieces of the message one by one—became popular (and I am secretly hoping they will once again become popular). The envelope for this letter reads, very sweetly, “My Dear this heart / That you behold, / Will break when you / These leaves unfold, / So my poor heart / With love’s sick pain, / Sore wounded is / And breaks in twain.”

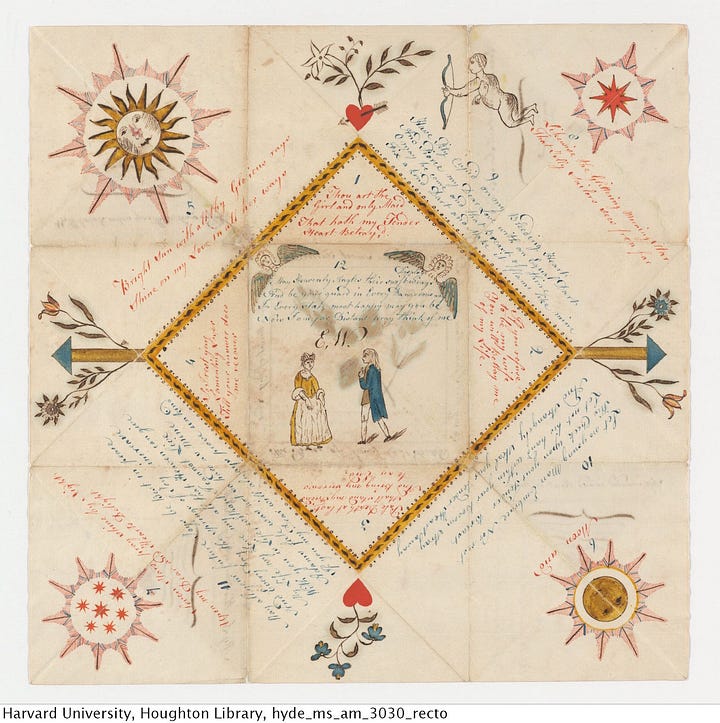

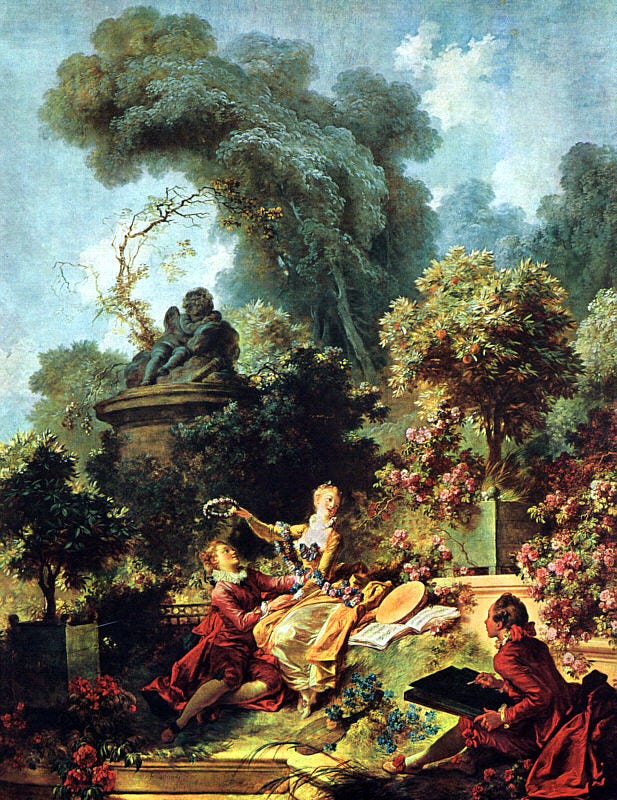

more puzzle purses! Jean-Honoré Fragonard, “Love Letters” from The Progress of Love (1770-2): French Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard was commissioned to paint The Progress of Love by Madame du Barry, mistress of Louis XV, for the pavilion of her château in Louveciennes. Its four canvases tell a love story from “The Pursuit” to “The Meeting” to “The Lover Crowned” to this painting, “Love Letters.” Unusually for paintings depicting a love letter, in which the letter often signifies the absence of the lover, the two lovers are together here, and very happily so. The scene, set in a sunny, lush landscape, surrounded by a profusion of flowers, a cocker spaniel at their feet, a cupid exulting beneath a statue of a goddess, creates an air of tranquility, contentment, and domesticity. But in spite of the beauty of the paintings, Fragonard’s Rococo style was being pushed out of favor by the new Neoclassicism, and du Barry rejected the series. Fragonard took them to his godfather’s villa in Grasse; they were later purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, then upon his death by Henry Clay Frick, and they remain in the Frick Collection today.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love (1770-2) Love letter pastries posted by voguely on Tumblr: The love letter emoji is probably my favorite emoji, and these pastries bring them to scrumptious-looking life. I found some recipes for making similar love letter pastries here, here, and here.

“Love letters only” mailbox on Whidbey Island, Washington: Where else do love letters go but their very own special pale pink mailbox that reads “love letters only”?

Letter from Frida Kahlo to Diego Rivera: Mexican painters Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera married in 1929, despite their age difference (Rivera was 21 years older than Kahlo) and size difference (Kahlo’s mother remarked that it was a “marriage between an elephant and a dove”). The marriage was a tumultuous one, marked by numerous affairs on both sides, and yet the bond, passion, and artistic affinity between the two painters could not be denied. I love how Frida writes in various colors of ink and sometimes includes little drawings in her letters, and I love the colorfulness of her writing itself, so full of vivid, poetic, bursting imagery: “…storm in the blood that comes in through the mouth—convulsion, omen, laughter, and sheer teeth needles of pearl, for some gift on a seventh of July, I ask for it, I get it, I sing, sang, I’ll sing from now on our magic—love.”

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Love Letter (early 1770s): Unlike Fragonard’s “Love Letters” above, this painting only depicts one of a couple, a woman, who instead of looking at the note sent with her bouquet of flowers or the papers on the desk looks directly at the viewer, coyly, as does the adorable little dog that sits behind her. The rich golden tones reflect off the folds of her silk dress, and the blush-pink of her cheeks, the ribbon of her cap, and her flowers adds a romantic sweetness.

Three Things I’m in Love With This Week Favorite Love Letters

The Letters of Abelard and Heloise: The love story between Peter Abelard and Heloise d’Argenteuil is one of my favorites in history, not least because of its tragic nature and because I always have a soft spot for forbidden love. One of the foremost philosophers in 12th-century France, Abelard came to Paris in 1100, where he studied at the cathedral school of Notre Dame. After quarreling with his teacher and proving himself able to defeat him in philosophical arguments, Abelard set up his own school, then eventually went onto become master of the cathedral school of Notre Dame in 1115. There, Heloise’s uncle and guardian Fulbert was a canon, and the young Heloise (traditionally held to be between fifteen and seventeen years old at the time) was already widely known for her scholarship and learning: she had become highly literate in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, thanks to her tutelage under nuns in the convent of Argenteuil, and wrote her own poems and plays. Fulbert made a deal with Abelard: in exchange for tutoring Heloise, the celebrity philosopher could stay at their home rent-free. Drawn to each other intellectually, student and teacher began a secret relationship, which could remain secret no longer once Heloise became pregnant. Enraged at discovering the relationship, Fulbert demanded they separate, but Abelard placated him by asking permission to marry Heloise, who agreed only on the condition that the marriage stay a secret, as celibacy was becoming the norm among the higher orders of the church. Heloise gave birth to a boy, whom they named Astrolabe after the astronomical instrument and left with Abelard’s sister. However, Fulbert began speaking openly about the marriage, causing tension with Heloise; Abelard had her moved to the Argenteuil convent to escape this unhappy home, and believing that Abelard had cast her off, Fulbert took revenge, sending men in the dead of night to castrate Abelard. Abelard became a monk, Heloise a nun, and from then on they could communicate only through letters.

In these letters, we see Abelard pained by his fate though resigned to it, trying to keep the conversation focused on theological topics, and Heloise caught between her profane passion for Abelard and her new, sacred duty towards God. In her first letter to him, there is a profusion of addresses, indicating this confusion—“To her lord, or rather father; to her husband, or rather brother; from his handmaid, or rather daughter; from his wife, or rather sister: to Abelard, from Heloise”—but in his reply, Abelard simply addresses her, “To Heloise, his dearly beloved sister in Christ, from Abelard her brother in Him,” as if clinging stringently to their new religious roles after the trauma of castration. Heloise perhaps speaks for all lovers who have put their passion into the art of letter-writing when she implores to Abelard, “While I am denied your presence, give me at least through your words—of which you have enough and to spare—some sweet semblance of yourself.”2

Wentworth’s love letter to Anne in Jane Austen’s Persuasion: Persuasion tells the story of Anne Elliot and Captain Frederick Wentworth, who were engaged eight years ago, when Anne was nineteen. Due to family members’ disapproval of Wentworth because of his lack of fortune and status, she broke off the engagement, to her regret—and Wentworth’s, too, it transpires. In those eight years, Wentworth has become wealthy and attained rank, while Anne, 27 now, inches ever closer to eternal spinsterdom. Circumstances bring them together once more, but Anne cannot tell whether Wentworth still has feelings for her, nor can Wentworth Anne, until he overhears her arguing that women are more constant in love than men. Unable to state his feelings for her in a room full of people, he instead pens her this letter, which contains the swoonworthy statement, “You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope.”

John Keats to Fanny Brawne, October 13, 1819: When I think of love letters, I always remember this love letter written by my favorite poet John Keats to his fiancée Fanny Brawne, about a year and a half before his death in February 1821 at the age of 25. I always remember it because of its extended metaphor of Keats’s love for Fanny as his religion and the feverishness with which he describes it: “I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion—I have shudder’d at it—I shudder no more—I could be martyr’d for my Religion—Love is my religion—I could die for that—I could die for you. My Creed is Love and you are its only tenet.”

Words of Wisdom

“I have nothing to tell you, save that it is to you that I tell this nothing.”

— Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse

Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse is broken up into various “figures” around the theme of romantic love, organized in alphabetical order. One of these figures is lettre, the letter, the love letter, which for so long has been an essential element in the amorous drama. Barthes refers, as he so often does in this book, to Goethe’s epistolatory novel The Sorrows of Young Werther: Werther is tragically, unrequitedly in love with Charlotte, his friend’s wife. Whatever he writes in his letters to her, whatever the various subjects and the surface words, his “musical theme” is the same: “I am thinking of you.” Contrary to the advice given by the Marquise de Merteuil in another epistolatory novel, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s Les Liaisons dangereuses, a love letter is not a tool, not a tactic, not an item of strategy in a game plan of seduction; it is a simple outflow of the heart, pure expression, “a relation, not a correspondence,” bringing together lover and beloved through their mutual thinking of each other by means of the letter, one by writing, the other by reading. This “thinking of you” is a way of making the beloved recur, bringing their presence to a sort of dreamlike life. I believe this is why writing a love letter can be so difficult for some—as far as a piece of writing goes, it does not require much imagination, for it does not say anything much more than, “I love you, I think of you.” And yet, what a delight—what a challenge—to vary that theme!

Poetry Corner

A Love Letter (To Li Zi’an)

Eating ice, chewing bark, wishes unfulfilled; Jin River, Hu Pass—only in my dreams. Although I’d split the mirror, I fear the magpie’s flight; although I’d play the qin, I resent the flying geese. By the well, paulownia leaves sing of autumn rain; beneath the window, silver lamps are darkened by dawn breeze. Where in all the world may one ask after a letter? My lines are cast all day, but the green river remains empty.

—Yu Xuanji (translated by Leonard Ng)

Yu Xuanji was a Chinese poetess who lived roughly from around 840 to 868. She grew up in Chang’an, the Tang capital, and at the age of sixteen was purchased by and became concubine to the censor Li Yi (Li Zi’an), who later abandoned her when she was nineteen due to jealousy from his wife. First wandering the mountains, she later found a home in a Daoist convent, a place where women had the chance to cultivate learning in literature and the arts and engage in a spiritual and intellectual community. However, at the age of 28, according to a rather sensationalistic account, she was decapitated for allegedly strangling a maid or Daoist novice named Luqiao.

As for her poetry, of which almost 50 poems remain, it is marked by a striking variety and vividness and shows an inner intensity of emotion, a keen eye for observing the natural world, and often a playfulness that belies her many hardships. Several of her poems are letters, and this one is poignant in that it reflects on what was probably her most significant relationship, which ended in an abandonment that must have affected her deeply. “Eating ice” (something I used to do when I was iron deficient—a longing for blood) and “chewing bark” were tropes commonly used to describe the behavior of widows, symbols of their great devotion to their husbands and the great extent of their sorrow after bereavement. The third line alludes to the story of a husband and wife who split a mirror when they parted, each keeping half as a sign of fidelity toward the other. However, when the wife had an affair, her half of the mirror turned into a magpie that flew off and informed the husband of the affair—Yu fears her own relationship meeting the same unfaithful end.

The fourth line references a 3rd century poem about the Emperor Shun, whose hands strum the qin (guqin) and whose eyes “send off returning geese.” The fifth and sixth lines, so richly detailed in their imagery, help create a picture of a woman awaiting a reply from her lover, staying up late into the dawn, listening to the melancholy rustle of rain and leaves. That the paulownia leaves “sing” is interesting also because paulownia wood is frequently used in China for the soundboards of string instruments, such as the qin mentioned earlier in the poem. But pine as Yu will, her letter receives no answer—she does not even know where to go to seek for it. As Barthes writes, the unanswered love letter turns the recipient into an “other,” a stranger, someone imaginary, a construction of the writer’s mind, a character who begins to overlap less and less with the actual beloved. Fish in medieval China were thought to bring letters, but however much Yu casts her lines, nothing bites, the river is empty.3

Beauty Tip

Write a heartfelt, handwritten letter to someone you love—try to dig deep into what is unique about your relationship with this person and what they mean to you, and feel free to decorate/aestheticize it and be creative with its form!

Lingering Question

Do you find modern forms of communicating (texting, calling, etc.) less romantic than letter-writing?

Dear readers, I thought it would be nice to do something sort of Valentine’s Day themed since that venerable holiday is coming up. In fact, my very first “real” post here was a Valentine’s-themed essay. If you enjoyed, please like this post, share with a friend, and write me a tiny love letter share your thoughts in the comments!

The Letters of Abelard and Heloise, translated by Betty Radice, 2003.

Notes on this poem from Lucas Klein and more about Yu by David Young.

Loved this piece,Ramya...so beautiful. I've always been a big letter-writer...to my closest friends;I've never been involved with any guys who were the least bit romantic,including my late hubby. That love letter from Frida to Diego was the coolest thing...I've always had a soft spot for Frida! I liked the Pennsylvania German puzzle purses as well...I lived in Pa. for a while in the 1970's and had never heard of these gems. I also loved your line,"...the millions of unsent missives that perch on the branches of one's heart"...what an awesome mental image.Thank you again for sharing with us...💕

What a sweet issue ❤️ Yes, I do think that modern forms of communication are less romantic than handwritten love letters. Definitely more convenient, but there's a deep level of vulnerability that comes with a handwritten love letter. I've only received one, but it's one that is so special to me.