Sonnets and Corsets

In dress and in verse, resisting the slouch

“Try to picture it as a slattern hemmed in by a corset, tempered by wisdom…”

—Hailey Leithauser, “Guidelines: Writing the Sonnet”

We’ve all seen it before, in period drama after period drama: a woman in 18th- or 19th-century underdress stands clutching a bedpost while a servant tugs on the laces of her corset, feet braced against the floor, pulling with all her might. “Tighter… tighter…” manages the woman through gritted teeth, “How can you possibly expect me to compete on the marriage market, arouse envy in my rivals, win a husband, be always on the edge of a delicate fainting spell, embody arcane and unrealistic beauty standards that liberated modern women totally never have to deal with, and generally be oppressed, without an 18-inch waist!?” Indeed, this scene of torture is so rote by now that we have come to expect it; it is nearly a genre in itself.

The conventional thinking of our time holds that corsetry was just another tool in the patriarchal toolbox, imposed upon women, who had little choice or say in the matter, to diminish their presence, sexualize them, proscribe to them what their bodies should look like, and literally keep them bound under the yoke of their subjection, too winded to protest or rise up. Reinforcing this idea are the myriad of Hollywood actresses who go on talk shows and gripe: “you can’t breathe,” “pinching me everywhere,” “women existed in that!” I’m sure the discomfort they experienced was legitimate1, and yet such comments only serve to shore up narrow stereotypes, failing to capture the nuances and benefits of this garment, which in the western world “was an essential element of fashionable dress for about 400 years.”2

In the same way as women have thrown off the shackles of their corsets, poets have thrown off the torture device of poetic form: no more being laced into pesky meters and rhyme schemes, no more syllable-counting, no more line-counting, no more hemming-in. Over the course of the 20th century, vers libre grew to become the dominant mode of poetic expression; today you would be hard-pressed to open a literary magazine and find yourself face-to-face with Alcaic stanzas, elegiac couplets, or that maid of all work, the ever faithful iambic pentameter—except ironically, or in so bastardized a version of the form that it seems related to it only tangentially.

I first turned to the sonnet a few years ago, during the pandemic. I had recently turned in my final project for an advanced poetry writing class and felt vaguely dissatisfied with the work I had done up to that point. I knew I was not where I wanted to be, and yet I didn’t know how to get there. Then, one hot morning in June, the impulse came to me, strangely and suddenly, to write a sonnet in blank verse. I had been reading Andreas Capellanus’s De amore, specifically the section in which Capellanus puts forth a false etymology of the Latin word amor from the word for “hook,” hamus, and musing on a recent experience that captured for me a certain truth in this false etymology. The sonnet, with the compactness of its fourteen lines and ten syllables per line, was like the heat and pressure that is exerted upon carbon deposits deep within the earth to create diamonds. Not that the process had yielded a diamond, exactly, but the clarity of what had emerged, the sharpness and toughness of it, the depth and multifacetedness the initial idea had acquired as it traversed those fourteen exacting miles, startled me. I had started with a rude chaos of thought, feeling, and image, and it had been made into something whole, something “more interwoven and complete,” to quote Keats, something that forced me to express what I never could have otherwise. I found my mind exerting itself to climb higher, to speak more truly, to delve deeper, to seek beyond its initial impulses, to listen to what lay within. Laced in, I was liberated.

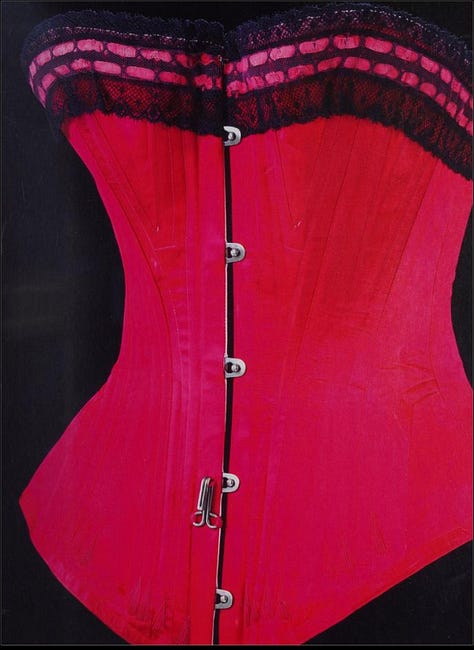

About a year ago, I decided to do something I had always wanted to do and bought a corset. At last, my long-cherished dream of outwardly manifesting my inner frail Victorian lady was becoming a reality. The adjustment was not without some discomfort. Like a wok, a corset must be “seasoned”—that is to say, your body and the corset must adjust to one another: the steel bones of the corset soften and mold to your body, while your muscles learn to compress and your organs shift.

More than that, you discover a slightly different way of being in the world. With your spine kept straight as a rod, whether you want it or not, you automatically have impeccable posture. You become more confident, more proper, more upright in your dealings with the world. My habit, whenever I took walks around the neighborhood, was to shrink unconsciously when a fellow human passed me in the street; wearing the corset—my armor of cotton coutil and flexible steel—made that physically impossible, and soon, even without the corset, the habit was eradicated. Every comfortable, squishy chair became distinctly uncomfortable, designed as they were (I now realized) for the abominable slouch of our spinally challenged age. I found that on days when I wore the corset, I was less prone to rotting in bed; I was more active, more ready to take on the challenges of the day. Hug-like, that light pressure around my abdomen held me in, the same way the sonnet form held in the sprawling mass of my inner life.

In both dress and verse, over the past century or so, we have found ourselves slumping further and further into an astonishing laxity. A few days ago I went to the library and observed that at least half the people were in sweatpants; one woman was even wearing what looked to be pajama pants. I know I’m a sartorially judgmental person, and I wish I wasn’t, but I can’t help but concur with Karl Lagerfeld: “Sweatpants are a sign of defeat. You lost control of your life so you bought some sweatpants.” Free verse, when carried out with the flabbiness that so often accompanies it, often employed by those who think poetry is simply an unrestrained outpouring of emotion, a sort of diary entry or therapy session, is the sweatpants of poetry. As T. S. Eliot says, “No verse is free for the man who wants to do a good job.”

Form is the pressure we exert on our days to give them meaning. In selecting for some values, we forget that we sacrifice others. To differentiate ourselves from our predecessors, we extol the virtues of what we perceive to be our liberty, failing to see it for what it really is: a lack of restraint. In my childhood, my parents used to drag me along to parties with family friends; because I was younger than the other children, I would speak little, and this silence made space for listening—listening led to learning, to reflection and an ability not to hold so dogmatically to one viewpoint or another. We are told to take up space, but the negative space you don’t occupy allows for newness, inquiry, knowledge-seeking. Shape is given not just by filling in but by carving out.

As the corset has declined in popularity as a staple of women’s wardrobes, it has been taken up by the storied ranks of high fashion, fueling a variety of artistic visions, from Vivienne Westwood’s punk-meets-Rococo 18th-century stays, to Jean-Paul Gaultier’s rebellious, bullet bra-esque Blond Ambition look, to Thierry Mugler’s leather, metal, and plexiglass carapaces, to Alexander McQueen’s darkly romantic, beautifully subversive renditions. Most recently, corsets came to the forefront of the public consciousness in the wake of the Maison Margiela 2024 Artisanal show, designed by John Galliano. The corsets here, worn by both men and women, were extreme, splicing top and bottom halves together with the narrowest margin the human waist could conceivably squeeze itself into. They appeared on a series of louche, waxen-faced characters, who stumbled through fog and shadow from the demimonde of 19th-century Paris, errant flâneurs of the night, crawling out of the convolutes of Walter Benjamin’s arcades. Their bodies were simultaneously striking and unsettling, grotesque and erotic—beauty taken to its limit, the threshold of the unreal.

In the Victorian era, the corset was a symbol of restraint, propriety, and discipline, a check on moral looseness. At the same time, exaggerating the curves that differentiated the female body from the male (or, in the case of male wearers, fashioning an alluring androgyny), it held an unmistakable erotic appeal. These two poles, restraint and eroticism, create a tension that is vigorous, vital, always on the verge of exploding. The erotic reaches its fever pitch when held back by the “almost” and “maybe” of restraint, just as restraint is awakened from prudishness and convention by the thrashing around of the erotic. After all, doesn’t the songbird flap more frantically for being in a cage?

It was precisely this energy that the first free verse poets sought when they overturned the reign of rhyme and meter, and yet their success was contingent upon their familiarity with received forms; they were in fact fashioning their own forms, and they had an intuitive understanding of formal principles that many poets today lack. They recognized that a transformation was needed, a reform of form, but not a total deformation of what has upheld the craft of poetry since it came into living memory.

After my first real sonnet, I found that I could not stop writing them. Exploring first the Petrarchan, then the Shakespearean, then delving into the more obscure variants—Spenserian, Miltonic, caudate—I progressed to inventing my own forms, breaking up the fourteen lines in different ways, playing around with different rhyme schemes, with half rhyme, eye rhyme, internal rhyme, finding that iambic pentameter was not rigid, stiff, and monolithic, but endlessly variable, dynamic, and productive.3 Form freed me.

Conversely, too much liberty can become oppressive. Indeed, perhaps it is not freedom itself we seek, but simply the freedom to choose our own restraints. The habits we build, the structures and routines we implement, shape our days and our lives, for better or for worse. True form is not dull or oppressive; it is the rigor that reanimates vigor, the ever-fruitful molding of an unrefined mass into what can rightly be called “art,” the extraction of beauty from everyday chaos.

If the corset fits, wear it.

—

My lovely readers, I apologize for the lack of post last Sunday—I shall endeavor to greater punctuality hereafter, so expect one this Sunday. If you enjoyed this essay, please be sure to like, and consider subscribing & leaving a comment! <3

Probably due to poor fitting, long hours on set, not being given enough time to adjust to it, etc.

Valerie Steele, The Corset: A Cultural History (2001).

For more on variations, see Strict Metrical Tradition: Variations in the Literary Iambic Pentameter From Sidney and Spenser to Matthew Arnold by David Keppel-Jones (2001).

Great comparison Ramya! Your piece is so humorous and meaningful. I believe it is not just with sonnets, even in writing an essay, the concept of simplicity has lent itself to lack of craft form just like sweatpants.

I can understand the need for a break, although I very much look forward to your form filled artistic writings. It is purely a delight read your creations!

What a lovely analogy between corsets and poetry structure! I am, however, a fervent support of free verse in certain situations (I know, I know - hear me out!).

Literature and poetry appears to be a dying art these days. Today’s youth seem to no longer possess the attention or tolerance for delayed gratification that is needed to properly read, digest and synthesize meaning from a poem or story. In that aspect, free verse absolutely has a crucial role (and benefits!) as a gateway to foster a younger generations’ interest in poetry. It is also particularly useful in its adaptability to the mediums of our time (as much as I detest Rupi Kaur’s particular brand of instagram poetry, you can’t deny that it has found wide success and recognition - a Keats or Tennyson poem just doesn’t have the instant relatability that “online viral-ness” demands).

Perhaps the best compromise is to require structure and meaning in poetry but to leave the expression to the author. Poetry, at its core, is a reflection of the human experience. If the central message is conveyed, could we not excuse a little metrical liberalism? Besides, as Mary Oliver noted in her book, “A Poetry Handbook: “free verse is not, of course, free. It is free from formal metrical design, but it certainly isn’t free from some kind of design”. ;)