No Cap

on all-lowercase internet writing

Young in years though I am, spiritually I have always been a grandma, so I was not surprised at my own feelings of discomfort, if not outright repulsion, at encountering prose written entirely in the lowercase. It is an affectation the thought leaders of my generation have developed—the “thought daughters,” the “Glossier intellectuals,” the “gen z philosophers,” the “academic cool aunts” the “metaphysical princesses” (okay, I made those last two up)—primarily of the female sex. If one of these all-lowercase essays were to be brought to life in girl form, it would be easy to imagine her with her poreless, dewy skin lying on the grass somewhere at the golden hour, in a casually expensive, frolicsome white dress, a Jane Birkin-esque basket at her side, a ribbon in her hair, writing in a leather journal in a studied pose of perfect, nymphic naturalness.

It is true that, female or male, our generation has thoroughly adopted the no caps style when it comes to texting and messaging each other. I remember, several years ago, going into the settings of my phone and purposely turning off auto-correction and auto-capitalization. To text each other with proper grammar, with periods and question marks and commas, with the beginnings of sentences and with proper nouns capitalized, in actual sentences, was like advertising your lack of cool. Visually, you were aligning yourself with the digitally clumsy Boomer generation. In recent years I’ve found myself adopting a kind of compromise—mostly lowercase with some punctuation, a properly capitalized sentence here or there—which must be a latent indicator of my now slow, now gradual, nevertheless deadly descent into middle age.

But I was surprised to see all lowercase afflict the essay form. Unless these essays were written on people’s phones—I can’t imagine writing an entire essay on a phone, but maybe, miraculously, people do it—writing something, especially something with pretensions to seriousness, something contemplative, something reflective, something that tries to say something meaningful, that tries to grapple with what words, even properly capitalized, are too often inadequate to grasp, that tries to traffic in the broader marketplace of ideas, in all lowercase is very difficult. It requires a continual dishabituation of learned conventions and the studied assumption of new ones.

If all caps shouts at you through the screen, no caps murmurs. If all caps is loud, aggressive, hostile, rude, no caps is quiet, passive, demure, sweet. All caps gets all up in your face, while no caps sits there with her ankles crossed, her hands folded neatly in her lap, waiting for you to start a conversation with her. To write in all lowercase is to broadcast yourself as cool, casual, accessible, deep in a low-fi sort of way. i’m just speaking to you from the heart, it says, i’m just showing you a page of my diary. this is just a silly little musing i had today under a tree. <3

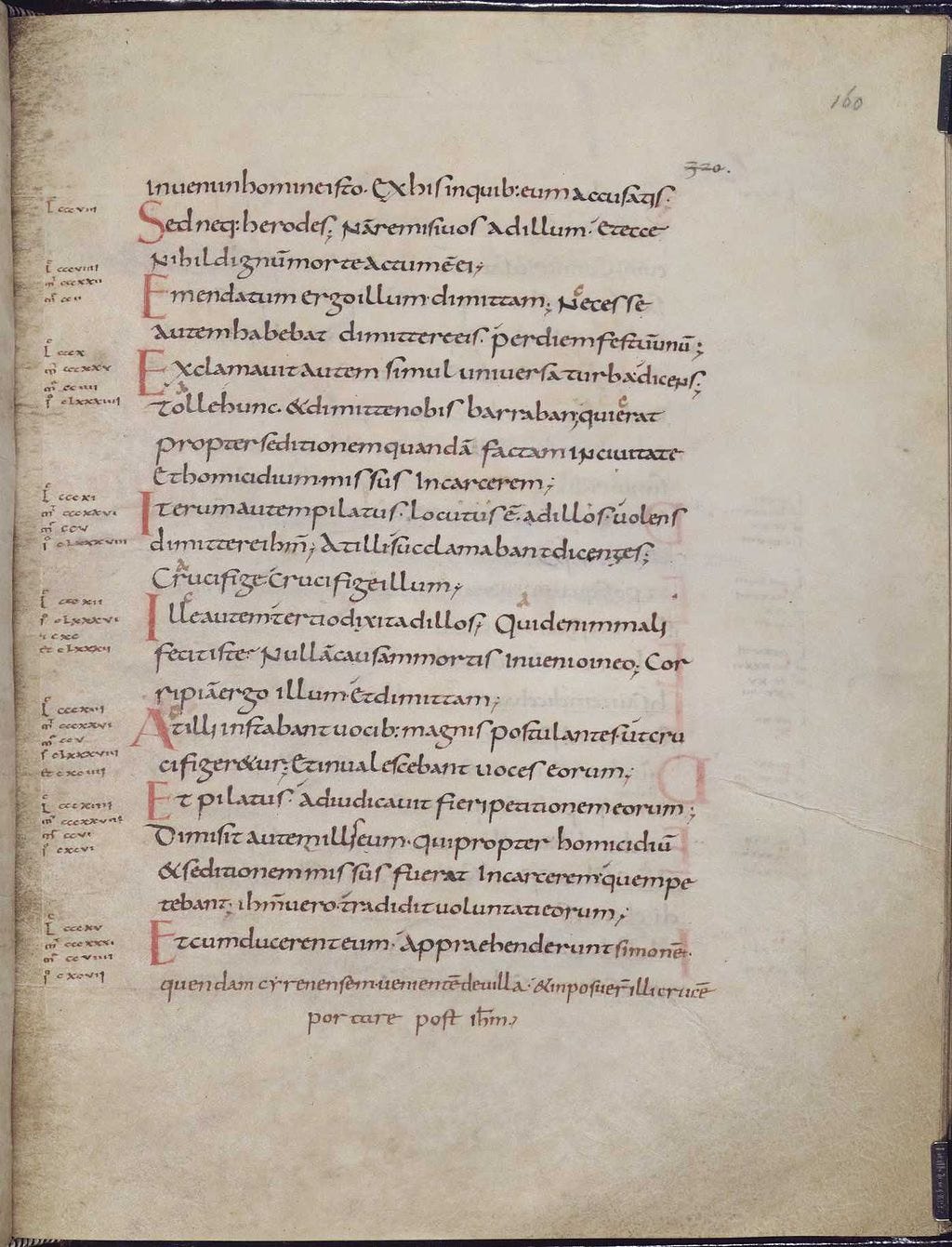

Why is it that it bothers me so much? After all, over the course of its history, shifts in capitalization have been largely arbitrary. The Romans only had majuscule; it wasn’t until the scholar Alcuin of York came to Charlemagne’s court in the 780s and spurred the development of Carolingian minuscule that the usage of lowercase letters was widely adopted. Things became more standardized after the invention of the printing press, and in the 17th century printers began to be influenced by the typographical conventions of German, a language in which all nouns are capitalized. Having taken to reading 18th-century novels over the past couple of months, like Samuel Richardson’s Pamela and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, I must admit there’s something about this Capitalization of Nouns that really touches my Soul, that catches my Fancy. It must have caught Emily Dickinson’s, too, because her poetry would not be the same were certain select nouns not capitalized, raised to the airy abstraction of purer Forms, as in “I dwell in Possibility—” or “I died for Beauty—”

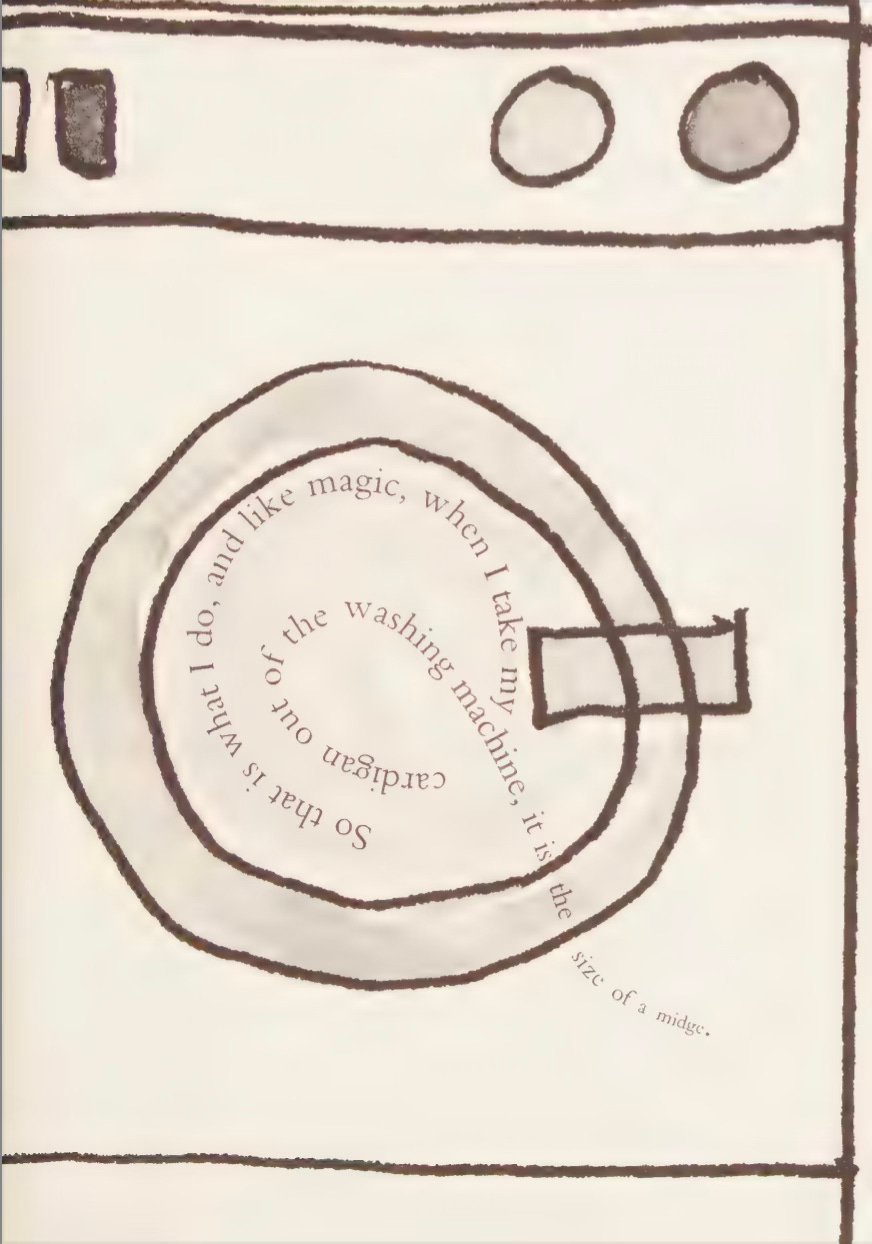

I think what disturbs me most about all lowercase is that it functions (or wants to function) as a visual marker of authenticity while actually being the exact opposite. Taylor Swift adopted it for two of her albums (“folklore” and “evermore”), self-conscious attempts to strip off the stellification of pop stardom and present herself as just a woman wearing a braid and a cardigan, strumming a guitar, humming through the woods. All lowercase is ubiquitous in the atrocious thing that dares to call itself “poetry” plastered over Instagram and hogging shelf space in bookstores, a signifier of poeticness for a poetry that—when you bother to read it, not just look at it—signifies nothing.

bell hooks and e e cummings are the two most frequently cited writers when one wants to find literary precedents for the adoption of all lowercase. hooks’ prose employs proper capitalization, but her name, always appearing with its “b” and “h” lowercased, is distinctive. For Gloria Jean Watkins, who took the pen name from her great-grandmother, that lowercasing was a way to emphasize the “substance of [her] books, not who [she was].” Her idea of the “oppositional gaze,” that the person—black, female, subordinate—who, looked at, was trapped in the gaze of an oppressor, could reclaim part of her power by looking back defiantly, is embedded in that lowercasing, which welcomes the reader to the page as an intellectual equal, a fellow-gazer and seeker of truth. e e cummings has rather the opposite case: the lowercasing of his name was a choice by publishers that Edward Estlin himself rarely partook of, but lowercasing of expected capitals abounds in his poetry. Because it is part of a larger project of breaking typographical and grammatical conventions, however, expressing a uniquely idiosyncratic approach to the written word, it makes sense, it suits style to substance.

Formality is something our culture has largely done away with. Men in suits have wrested themselves free of the chokehold of ties, refusing to be led by the leash; nobody really dresses for dinner; sweatpants are ubiquitous. With lowercasing, the eye, not needing to make the subtle leap a capital letter requires, is handed a more “frictionless” experience—but so is the brain. Sit up, I want to say when I encounter an essay in all lowercase, stop slouching.

Most egregious is the lowercasing of the vertical pronoun I. Of all the pronouns in English—we, he, she, it, you, thou, they—only the first person singular is capitalized wherever it appears, whether at the beginning of a sentence or the middle or the end. One letter, long and vertical, it stands as proudly as a pillar, a solid column of marble supporting an edifice of emotions and reflections, pondering and wanderings, trains of thought and flights of fancy. It’s a watchtower from which one can survey the world, maybe a ladder that, through the act of writing, actually helps us climb out of ourselves, the bottom rung rooted in our egos, the top rung ascending to a higher heaven.

As a child I used to love the book Utterly Me, Clarice Bean by Lauren Child, which took a picture book heroine and put her in a chapter book, upping the substance while still having a bit—actually a lot—of fun with the style. Words varied in size, lines sometimes tilted sideways, letters edged out of their neat alignments, elbowing each other or drifting off into waves and circles, falling and spilling and expanding and shrinking, undergoing Protean shifts in font. I wish we could capture more of this sort of playfulness when writing on the Internet, where experimenting this way is theoretically far easier than it would be in print and yet remains shockingly unexplored. As any good typographer knows, the way letters look does change the relationship between signified and signifier. The scrawl of a handwritten note conveys intimacy, love, warmth, the immediacy of feeling. A multicolored birthday banner is a harbinger of fun. A corporate slogan on a billboard broadcasts whatever it’s trying to sell you.

“There has not yet been any writing that inscribes femininity,” wrote Hélène Cixous in 1975.1 Maybe all lowercase writing is the “writing that inscribes femininity”; at least, it has the appearance of being so. Cixous argues that the history of writing has been wound up with the history of reason, a “phallocentric tradition.” The capitalized “I,” then, might merely be seen as the phallic center around which such writing orbits, and the lowercase “i” deflates it, puts it in its proper place. To convey a woman’s consciousness in Molly’s monologue at the end of Ulysses, Joyce reverts to a prose without punctuation, an endless, fluctuating flow of thought and feeling.

But I remain unconvinced that either this or all lowercase writing liberates the potential so sought for in the elusive écriture féminine. Writing according to conventionalized codes of style allows us to not get so caught up in surfaces; after all, women have been circumscribed for so long by their surfaces. Maybe it’s in the text, not on it, that we should be seeking authenticity, immediacy, beauty. Who knows how strangely, how wonderfully, our voices might bloom then?

Dear readers, I hope you enjoyed reading this essay! If it brought joy into your life, changed the way you look at something, or felt intellectually enriching to you, I would really appreciate it if you hit the like button, restacked, shared with a friend, sent this post via carrier pigeon across the ends of the globe. As always, I love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

“The Laugh of the Medusa,” translated by Paula and Keith Cohen in 1976.

FINALLY! You've hit the nail on the head. I am now subscribed and will continue to follow your essays. Sometimes the avant garde works for certain aspects but overall this new style of writing feels like things are changing on the horizon. I too, have my traditional style, but reading this gives me hope!

Thank you for your thoughts.

This is such an insightful essay that delves into our generation's shift from capitalisation . It says a lot about the current generation's relationship with formality. But, using only lowercase seems like a liberation from conventions. When I read all lowercase, I think of it as a raw and unfiltered thought, something intimate. Really a wonderful essay!