Friday Frivolity no. 35: Some Reflections on Furniture

and Beethoven and oysters and hot cockles

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

Some Reflections on Furniture

There comes a point in everybody’s life when one must begin to think about furniture. Hitherto the bed, the sideboard, the armchair in the corner with the sagging seat, the dresser whose drawers one opened and shut a thousand times, the desk, the nightstand, were taken for granted and never thought of much. They disappeared into the background of one’s life, objects which one ran around as a child but never stopped to look at, things which one tried not to scratch, scrape, break, impair, damage, or abrade, for fear of the parent’s stern look, wagging finger, or ineluctable scolding, entities that were just there somehow, there for the coffee cup or the weary body, significant only in function and hardly noticed.

Recent entrance into married life has changed my perspective on furniture. Setting up house together, little by little, my better half and I begin to ask ourselves how we want to fill our spaces, how we might unite form and function in such a way that a house becomes a home, how—to tweak a sentiment from Coleridge—to put the best things in the best order such that some kind of domestic poetry sings forth.1 What is this place that we are fashioning together, what kind of shape do we want it to take on, how can it be conducive to our happiest living together, what kind of dreams will it make come true or help breathe life into, what moments will it serve as backdrop to, what sort of stage does it set?

Being fond of old things, which generally can’t be beat nowadays for price, quality, beauty, variety, and functionality, we hit up an estate sale a couple of months ago and made out like bandits. Chief among our spoils were a wooden kidney-bean shaped desk that had been entirely engulfed by stacks and heaps of china, and a pair of handsome, green velvet-upholstered dark wooden chairs, ornately carved, their backs inlaid with flowers, their feet in the shape of lion’s paws. Now whenever I sit on one of these chairs in front of this desk, which has become my writing desk, I remember my husband picking his way over a treacherous path of ice and snow, making use of his masculine strength and all those years of working out to carry our new old treasures from the estate to the car, the two of us somehow managing to lift that desk up the stairs and into our apartment, my husband cleaning and polishing it until it looked good as new and smelled beautifully of orange oil. All our newlywed happiness and love seemed to have become a part of it, all his encouragement of my writing and our cherishing of each other’s dreams, the warm glow and thrill of beginning to build a life together.

A couple of weeks ago we went to Brimfield, the famed flea market, where a man showed us some superlative antiques—18th century chests of drawers with delicate inlays and marble tops, a fine 19th century china hutch—explained to us the difference between flat fronted and serpentine chests, and told us about how certain elements, like handles and locks, could be customized back in the day depending on the customer’s budget. We had to pass over his trove for pecuniary reasons, but the knowledge he’d so kindly and enthusiastically imparted served us well: we left the market with a mahogany dresser we now knew was serpentine, with rows of drawers on either side and a row of smaller drawers down the middle, beautiful in form, fruitful in function, and a miracle that we managed to fit it into the car.

If the architectural elements—the walls, the floors, the wainscoting, the crown molding and what have you—are the bones of a living space, then surely furniture must be its muscles. At the Museum of Fine Arts with my friend a few days ago, we stumbled into the American wing, where we were met by a preponderance of early American furniture and decorative objects. Beautiful clocks painted with the goddess Aurora ablaze in her sun-hauling chariot, tabletops and drawers inlaid with conch shells and urns, Chippendale bonnet-tops, desks with what seemed to be hundreds of little slots and compartments and cubbies and nooks, mirrors atop which gilded birds perched, games tables with cabriole legs, paw feet and scrolled armrests. I learned of the Newport “block and shell” style, pioneered by John Townsend, where a pattern of alternating concave and convex shells mark out the blocks that make up a piece. One piece that tickled me particularly was a little tea table from 1760 with scalloped edges, each scallop perfectly designed to hug a saucer.

Everyday things that delight through both aesthetic beauty and practical perfection, relinquishing neither in favor of the other, things that age well and accrue history and memory, things that are made with care and kept with care, things that are worthy of time’s blessings, things that one can have and love over a lifetime and pass down to one’s children—these are what I love most of all. If there is one benefit to living in an era in which most things are mass-produced and made to be thrown away in a year’s time, it is that we may have a better appreciation for handcraft, for the purposeful, human making of meaningful things.

The home I grew up in had lovely furniture, made by hand and of beautiful wood, but it was very plain, Shaker-style furniture, not nearly interesting enough for a child with a more fanciful eye. Its plain, honest appearance, its minimalism and simplicity, made it fade into the background, useful but silent on the subject of its own beauty, like a pretty woman who wears no makeup and dresses as inconspicuously as possible. Then again, to the untrained eye (or the eye that fails to look closely), no makeup and “no makeup” makeup appear indistinguishable, and the dress that looks simplest on the surface may belie its true complexity; as David Pye writes, “Our environment in its visible aspect owes far more to workmanship than we realize.”

There is a magic in the making of beautiful things, in the care and skill, the knowledge and dedication. When beauty is lent to an everyday object, it seems to become more solid somehow and is a source of endless joy. It makes me think of these lines by André Breton, which have always stuck with me from Bachelard’s Poetics of Space:

The wardrobe is filled with linen There are even moonbeams which I can unfold

May we all live in spaces where we can open a drawer and discover a moonbeam or two hiding under the papers and all the long-forgotten things, where a sliver of silver slips out from a crevice and greets us like a smile.

—

I really love this post by Matt Kenney from a furniture maker’s perspective on the feelings he wants his pieces to evoke:

The true reason that furniture endures is that it has meaning in the lives of those who own and use it, because it’s special to them.

As always, there’s so much inspiration to find on Thanks It's From where Nora dredges up the best on eBay, and I loved the vintage and secondhand furniture issue that came out earlier this month. I also got a ton of inspiration from Robert Khederian’s newsletter Second Story, especially these tips from interior designer Max Sinsteden, and from Katie Elliott’s reflections on the Arts and Crafts movement here.

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

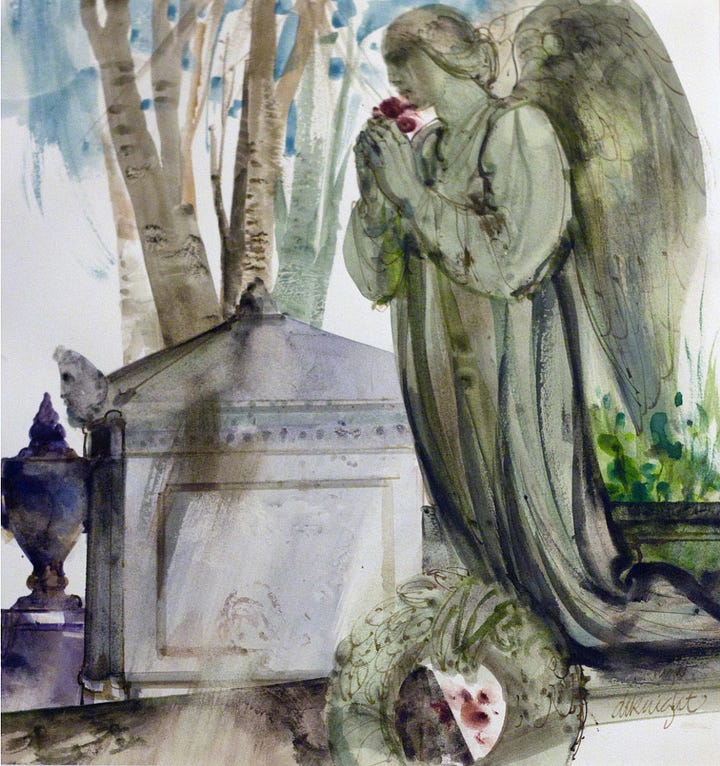

Avel de Knight, Saint Sebastian (1991): Avel de Knight (1923–1995) was an African-American painter, teacher, and art critic who produced this lovely watercolor and ink drawing towards the end of his career. His work often has a sketch-like, almost unfinished quality to it, which doesn’t detract from the work but instead makes it more dreamlike and poetic, like images left behind from a half-forgotten memory.

Avel de Knight, Charbourg (1985) and Untitled (1987) Alberta Tiburzi shot for Rocco Barocco in 1979: Fashion designer Rocco Barocco got his start in Rome in the 1960s, and his brand took off due to its fruitful combinations of avant-garde experimentation with high glamor, sensuous femininity, classic tailoring, and bright, bold colors and prints. Here I love the dynamism of this yellow and purple dress worn by model Alberta Tiburzi, the purple drama of her red underskirt, large purple hat, and the purple shadows she casts on the wall, almost in the pose of a female matador.

Mu’in Musavvir, Amorous Couple and Servant (1696): One of the most important and prolific Persian artists during the Safavid dynasty, Mu’in Musavvir produced exquisite miniatures illustrating people, events, histories, and epics like the Shahnama. In the 17th century Persian art world, there was significant competition among artists, leading each artist to develop a distinctive and recognizable way of handling his brush. Mu’in’s brush was fluid and dynamic, producing looser lines. I like the yellow background of this scene, the slight tree that sways behind the couple, the delicate details of their clothing, like the woman’s colorful striped pants and pink overgarment. She and her lover must have been so used to servants as to render them nearly invisible, because having someone watching my intimate moments that close up would make me pretty uncomfortable.

Elderly garden enthusiasts in an iris garden in Concord, Massachusetts, photographed by M. William Woodbridge for National Geographic in 1959: I love the enthusiasm of these, well, enthusiasts, standing in the rain and taking notes in a springtime garden blooming with yellow, white, and purple irises, following in the tradition of their fellow Concord nature-lovers, Emerson and Thoreau. The gentleman courteously holds an umbrella over one of the ladies who are jotting down on their notepads—what? If it were me, I know, it’d be poetry.

Jean Honoré Fragonard, A Game of Hot Cockles (ca. 1775-80): I love the rococo sweetness of Fragonard, whose paintings to me are like little French bonbons or cream puffs. Here, however, he takes a little detour to Rome, which gave him the inspiration for this painting’s vivid colors and the scenery of its background. These men and ladies are certainly not afraid to get their precious silks dirty, and their fine attire belies the naughtiness of the game they partake in. Apparently, hot cockles was a game in which one person placed their head in another person’s lap while a third person spanked their bottom. The challenge was to guess who had spanked you. The French nobility really did have a lot of time on their hands.

Erwin Poell, cover design for n+m (Naturwissenschaft und Medizin) in 1964: Who says that science can’t be beautiful? I recently came across a series of vintage covers for the German science journal n+m designed by graphic designer and typographer Erwin Poell (1930–) in the 1960s and 1970s. Poell started his own design company in the 1950s, and he spent over three decades of his career designing postage stamps for the German Federal Post Office. Most of these covers embrace minimalism, but here nature in all her intricacy and color takes over.

Oscar de la Renta, Spring 2015 Ready-to-Wear: In his Spring 2015 collection, Oscar de la Renta embraced spring in all its glory through beautiful pastel pinks and bright greens, robin’s egg blues and buttercup yellows, lace and embroidery and, yes, florals. Green is not a color I wear a lot, but if I had to pick a shade, it would be this one.

Oscar de la Renta, Spring 2015 Flowers photographed by Kelli Soukup: Because who doesn’t need a touch of pale pink dreaminess in their life?

Devon Aoki backstage at Fendi’s Fall 2001 show: This collection may have been for fall and winter, but the makeup paired with it on the runway, bright yellow eyeshadow melting into copious pink blush and bright pink lips, says nothing but spring to me.

some makeup inspiration from Devon Aoki in the 2000s

Three Things I’m in Love With This Week

Beethoven, String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp Minor, op. 131: At the beginning of this month, I was rendered speechless by a performance of this string quartet, one of Beethoven’s sublime late quartets and, I think, the greatest of them. Beethoven, too, considered his String Quartet No. 14, composed a year before his death, to be his most perfect work, and though the late quartets’ genius perplexed contemporary listeners, Franz Schubert was so amazed he said, “After this, what is left for us to write?” and promptly died the next day.

In seven movements played without a pause, the piece begins with a contemplative, mournful fugue, then shifts into liveliness, vivacity, counterpoint, and the dazzling majesty of the finale in which the fugue is revisited once again. Was it his deafness that enabled Beethoven to cast a bucket so deep into the well of his own soul?

Vincent d’Indy, Istar, Variations Symphoniques, op. 42: Maybe it’s unfair to French composer Vincent d’Indy to have him follow Beethoven (and Beethoven’s best, at that), but it turns out that one of his biggest influences was Beethoven anyway, so maybe he’d be happy. I’d never heard of d’Indy before this piece was mentioned in a book of literary criticism I was reading but, upon listening, I liked it immensely. It takes inspiration from the Assyrian myth of Istar (or Ishtar or Inanna), in which the goddess of love and war descends into the underworld, which is ruled by her sister. At each of its seven gates, she is instructed to remove a garment or a piece of jewelry, stripping her naked and shorn of her power. d’Indy’s seven variations enact this: the first variation is the most elaborate and the seventh the least, simple the undressed, unadorned theme.

“Chair Times” – A History of Seating: How much is there in a chair? A lot, it turns out, watching this video from the Vitra Design Museum, in which a collection of chairs from the 19th century to the present day is assembled, somewhat hodgepodge, in a single room. More than mere places to park your rear, chairs are sculptures, works of art, repositories of history and memory and technology, spots for thought and friendship and conversation, miniature buildings. Some of these chairs have wheels, some have legs, some have stands; some have arms that look like a warm embrace, some have arms that look like they want to punch you; some are made of metal, some of glass, some of wood; some conform to the shape of your ass, some are not shy about their intent to make your tailbone ache; some are like tiny grottos you can crawl into to hide from the world; some are deceptively simple.

Take Thonet’s No. 14 chair, the classic café chair, with the stripped-back elegance of its back formed of two bent wood curves, its woven cane seat, its four gently tapering legs. Its rounded curves make it seem friendly and inviting, its simplicity makes it able to be ubiquitous without drawing too much attention to itself; armless and light, it is eminently stackable, and the holes in its woven seats allow spilled liquids to fall through without leaving any mess or fuss. Handily enough, Vitra makes a poster of its chair collection, in case you wanted a present for the chair enthusiast in your life.

Words of Wisdom

“Rather than take a scary baby step toward our dreams, we rush to the edge of the cliff and then stand there, quaking, saying, ‘I can’t leap. I can’t. I can’t….”

—Julia Cameron, The Artist’s Way

Little by little, I’ve been taking those scary baby steps. I still do find myself quaking at the edge of the cliff on occasion, especially when I read all the great writers I admire so much, but the satisfaction of writing a little everyday, of being disciplined, of that discipline sparking more inspiration than if I’d just sat around twiddling my thumbs, makes me keep putting one foot in front of the other.

Poetry Corner

Oysters

Our shells clacked on the plates. My tongue was a filling estuary, My palate hung with starlight: As I tasted the salty Pleiades Orion dipped his foot into the water. Alive and violated They lay on their bed of ice: Bivalves: the split bulb And philandering sigh of ocean. Millions of them ripped and shucked and scattered. We had driven to the coast Through flowers and limestone And there we were, toasting friendship, Laying down a perfect memory In the cool of thatch and crockery. Over the Alps, packed deep in hay and snow, The Romans hauled their oysters south to Rome: I saw damp panniers disgorge The frond-lipped, brine-stung Glut of privilege And was angry that my trust could not repose In the clear light, like poetry or freedom Leaning in from the sea. I ate the day Deliberately, that its tang Might quicken me all into verb, pure verb.

—Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney is always so good with the sounds of words, with rich clusters of consonants and vowels that echo, with images grounded in the vivid, earthy specificity of their sensuous detail. In this poem, he unites that with a lovely, lush lyricism—for days I haven’t been able to get out my head the line “My palate hung with starlight.”

But the simple, delicious pleasure of the oysters doesn’t last. So familiar with the violent upheavals of late 20th-century Ireland, Heaney can’t help but be attuned to the violence of other contexts: the oyster shells are “alive and violated… split… ripped and shucked and scattered,” and the ocean is a philanderer, a violator, a rapist.

Stanzas of delight and contentment and happiness alternate with stanzas where something more troubling, menacing, or complicated comes along. In the third stanza, Heaney recalls the “perfect memory” of going to the coast, driving past flowers on a beautiful day, the “cool of thatch and crockery” and the warmth of “friendship.” Yet in the next stanza, like an intrusive thought, he can’t help but recall the Romans, those conquerers of old, and how oysters were their “glut of privilege.”

Heaney hates that he keeps doing this (“angry that my trust could not repose”), that good sensory experiences and good memories are interrupted continually by insinuations and histories of violation and conquest. Finally, he decides to be deliberate about it and eats that perfect day “deliberately,” hoping to become “verb, pure verb”—pure sensation, pure feeling, pure presence and joy and aliveness.

Beauty Tip

Grow your own herbs! Earlier this week, I harvested some basil we’d been growing and made pesto, and it tasted so good and so fresh my husband said, “What are we doing with all these empty windowsills? We need to start growing more basil ASAP!”

Lingering Question

If you were a piece of furniture, what would you be? I think I’d be a rocking chair, just because they’re both fun and comfy.

Dear Readers, Happy Friday! I hope you enjoyed this one! Please let me know your thoughts in the comments, like this post if you enjoyed, share with a friend, and don’t forget to subscribe to Soul-Making for more <3

“I wish our clever young poets would remember my homely definitions of prose and poetry; that is, prose—words in their best order; poetry—the best words in their best order.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Thank you for including me 🤎🤎🤎