Friday Frivolity no. 34: I Love Lilac

Flower of first love, New England, and Abraham Lincoln

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

I Love Lilac

In most versions of the story, the pipes of Pan are made of wetland reeds. But what if, fleeing the wild, half-goat god, the wood nymph Syrinx metamorphosed instead into a lilac tree, one of those bushes, blooming in a profusion of small purple flowers, that erupts in gladness every spring? After all, she lends her name to its genus, Syringa, on account of its hollow branches. The wood of a lilac is striped with purple—white rings alternate with watered-down violet, green, and the occasion Tyrian, as startling as Elizabeth Taylor’s supposedly lilac-hued eyes. A lilac pipe, I imagine, would make a sweeter sound than a reed pipe; it would make a shimmering, pale purple music, a music drenched in moonlight and perfumed with a fairy’s breath.

Lilacs made their way through Europe and into North America from Ottoman gardens in the late 16th century. Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, ambassador to the Ottoman Empire under the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, had a passing interest in herbal medicine and in flora and fauna. Perhaps more famous for introducing the tulip and the Angora goat to northern Europe, in 1562 he sent lilac cuttings to Dutch botanist Carolus Clusius. In a letter, he observed that “the Turks are very fond of flowers, and, though they are otherwise anything but extravagant, they do not hesitate to pay several aspres for a fine blossom.” It seemed that many Europeans, too, could not fail to recognize the value of the lilac’s “fine blossom,” and in the following decades the lilac began to take hold, particularly in English and French gardens.

What to do when the world tumbles into tumult and terror, but look to the lilacs? That was what 19th century horticulturalist Victor Lemoine and his wife did at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Living in the Lorraine region, which lay at France’s border with Germany, Lemoine and his wife found themselves unable to safely leave their beloved nursery, where Lemoine had been breeding new varieties of begonia and fuchsia. From his time in Belgium, Lemoine had a cutting of a rare double lilac—a lilac with eight petals to a flower instead of the usual four. Yet the cutting’s color was a weak, watery blue. Lemoine selected other lilacs whose hues were far more pungent and mixed them with the double lilac, using his decades of experience (and not the studies of Darwin or Mendel, too new to be widespread) to guide him. His wife, Marie-Louise, was a necessary part of the whole operation: her small hands aided her in the delicate task of standing up on a ladder, pollinating the tiny blossoms with tiny tools. As the years passed, their son and grandson joined the operation, which ended up producing around 200 varieties of beautiful, intensely scented blooms in a spectrum of pink, blue, purple, and white. Maybe it was one of these varieties Van Gogh delighted in at the hospital garden in Saint-Rémy, one of these varieties that Manet plucked for his joyous still lifes.

In America, we can thank two of our Founding Fathers, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, for proliferating the lilac. Both transplanted European flowers and shrubbery into their gardens at Monticello and Mount Vernon respectively; indeed, on March 3, 1785, Washington made a little note about his lilacs in his diary. It was also American poets who best immortalized the lilac in verse. Commemorating a different President, Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman penned “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” In April 1865, the poet got word of Lincoln’s assassination while he was visiting his mother’s home in Brooklyn. In his shock and grief, he stepped outside to take a breath. Looking around at the dooryard, he saw, as he later recalled, that “there were many lilacs in full bloom. By one of those caprices that enter and give tinge to events without being at all a part of them, I find myself always reminded of the great tragedy of that day by the sight and odor of these blossoms.”

In Whitman’s elegy, the lilac, with its “heart-shaped leaves of rich green” and “many a pointed blossom rising delicate” and “perfume strong,” is a symbol of the spring season in which Lincoln died, a season of so much life and so much death, so much joy in the natural world and yet so much sorrow in the human world, the world both of public affairs and private feelings. The poet breaks “a sprig with its flower” and imagines the procession of the coffin, imagines giving the sprig to the coffin as an offering. But to bring just this one sprig to just this one coffin is not enough: “Blossoms and branches green to coffins all I bring.” For the offering is to death itself, and so the poet comes with “loaded arms… pouring for you / For you and the coffins all of you O death.” Indeed, it is fitting that lilac should be the color permitted in the Victorian era for “half-mourning”—after a prescribed period in which a widow can wear nothing but black, she makes her journey back to the realm of full color by limping through the purgatory of Via Syringa. Yet for Whitman, the lilac ultimately emerges as a symbol of life’s triumph over death. Our last image is not of the plucked lilac sprig or of the armfuls of lilac offered to death but of the lilac “there in the door-yard, blooming, returning with spring.” Spring will come back, the star will rise in the firmament once more, the lilac will spread its heart-shaped leaves, and the song of the hermit thrush will once again join the poet’s.

Triumphant also are Amy Lowell’s Lilacs, which become a symbol of “this my New England. No mourning (or half-mourning) sprigs are these. These lilacs are home to “orange orioles” and “sparrows sitting on spotted legs,” they watch the daily comings and goings of preachers and schoolboys and housewives and cows, they have left their faraway Eastern origins and are quiet and subdued and suburban now, reticent and yet content, spreading their blossoms by the doorways of Maine and New Hampshire, Vermont and Connecticut, breathing in the salt sea air from Cape Cod to Rhode Island, “making poetry out of a bit of moonlight.” In New England, it is not the lilac’s leaves that are heart-shaped, it is our hearts that are the shape of lilac leaves. A New Englander myself, when I walk along the streets of Boston and see lilac bushes in full bloom under the awnings of apartment buildings and on street corners, I cannot help remember the lines

Lilac in me because I am New England, Because my roots are in it, Because my leaves are of it, Because my flowers are for it, Because it is my country And I speak to it of itself And sing of it with my own voice Since certainly it is mine.

And then who can forget the opening of “The Waste Land,” which always emerges at the beginning of spring, breaking forth from the soil of my memory to bloom again? It is lilac that emerges, lilac that revolts against the cruelty of the month and the dead land, lilac’s roots that are stirred, lilacs that are the axis of all this memory and desire:

April is the cruellest month, breeding Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring Dull roots with spring rain.

Lilacs never again appear in Eliot’s poem, and yet I like to think that their silent presence accompanies it, quiet lilacs blooming by the doorway, always ready to offer a sprig of hope, a sprig of love and consolation and friendship to one in need.

Mood Board of the Week

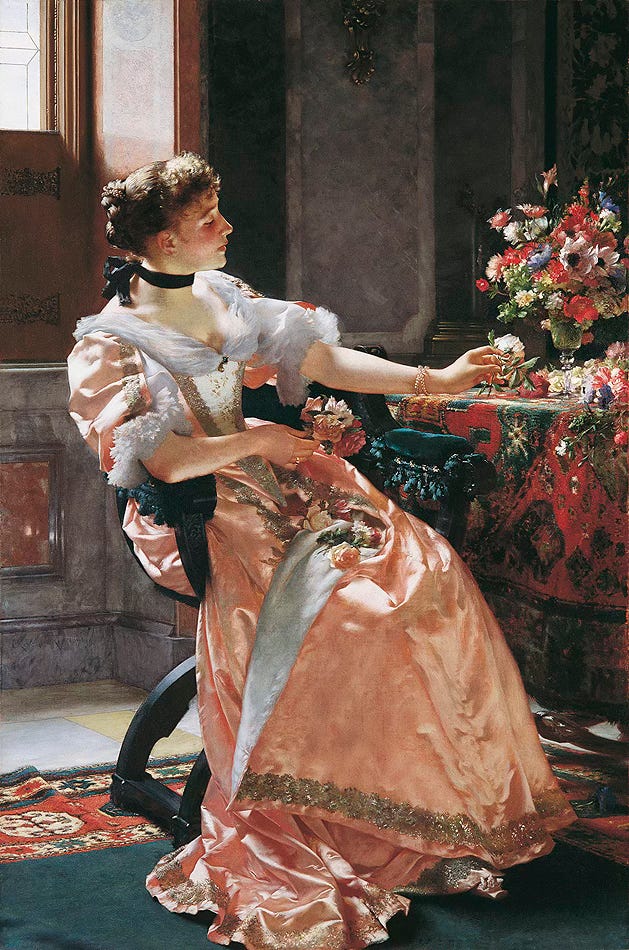

Władisław Czachórski, A Lady in a Lilac Dress with Flowers (ca. 1880): Władisław Czachórski (1850–1911) was a Polish painter who worked mainly in the Academic style. His favorite subjects were scenes from Shakespeare, still lifes, and portraits of elegant women in richly rendered interiors. This painting is no exception: I can practically feel the smooth silk of the lady’s fashionable lilac-colored dress, which catches the soft light from an unseen window. She reaches to pluck a pink flower from a towering, monumental vase of them; beneath her arm, more flowers are bunched in a basket, spilling out onto a marble-topped table.

Amal Clooney in an Atelier Versace gown at the Venice Film Festival in 2017: I love the sleek, chiffon elegance of this lilac gown on Amal Clooney, which looks both classic and contemporary, completed by Old Hollywood hair and makeup and accessorized with, well, George Clooney.

Claude Monet, Lilac Bush, Grey Weather (1873): The flower most associated with Monet is the water lily, but he was no less adept at observing the lilac, which grew in the garden of his first home in Argenteuil. He depicts them here in grey weather, in another painting in sunny weather; in both paintings, the human figures lying in the shade of the lilacs seem almost an afterthought: it is the blossoms themselves that take center stage, whether in muted hues or brighter.

Claude Monet, Lilac Bush, Grey Weather (1873); Lilac Bush in the Sun (1873) Picture of lilacs I took this week: In this first week of May, the lilacs were in full bloom, spreading their grace and elegance in thick beautiful clusters of blossoms. Their heart-shaped leaves seemed to be like little love letters from spring.

Aleksandr Kryushyn, Still Life with Tea and Lilacs (2020): Ukrainian painter Aleksandr Kryushyn combines elements of impressionism and realism to depict rivers and villages, sunny mornings and spring bouquets. I love the serene garden setting of this painting, where tea things sit on a creamy tablecloth, over which a lilac bush spreads its sweet scent, the two white chairs empty, perhaps, for you and I.

The Purple Hotel in Lincolnwood, Illinois, photographed by Chris Bentley: There are two competing accounts of how The Purple Hotel got its purple. Both begin with Hyatt’s desire to open a flagship hotel in the Midwest. Architects Hausner & Mascai were contracted; according to Mascai, the hotel’s wealthy owner, A. N. Pritzker, found the idea of grey bricks decorating the façade of this mid-century modern building a little too dull, and so had them painted this striking shade of lilac. According to another account, the lilac was a mistake—the intended color had been dark blue. Whatever the case, the peculiar purple of the hotel’s exterior was eye-catching… until it eventually became an eyesore. Famed performers like Barry Manilow and Roberta Flack and guests like Michael Jordan gave way to prostitutes and mobsters (Allen Dorfman was murdered in the parking lot in 1983) and to the likes of the Midwest Fetish Fair. In 2007, its health code violations caught up to it; there was a valiant effort to restore it, which failed, and in 2013, the lilac and its mold were finally demolished.

Vincent van Gogh, Lilac Bush (1889): Van Gogh painted this lilac bush in May during his time in the asylum of Saint-Rémy—on May 8, 1889, van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself to the asylum, months after he had mutilated his ear during a breakdown in December, and his first paintings there took inspiration from the hospital’s garden. Here the inky ultramarine of the sky sets off the light greens and light purples of the bush. All is energy, activity, motion in the quick, short brushstrokes that gather into a May abundance.

Zac Posen Spring 2017 Ready-to-Wear: I love the springtime elegance of this lilac shirtdress by Zac Posen, with its knee-length skirt, its tie waist, its neat row of buttons, its wide collar, and its easy, breezy sleevelessness, perfect for an afternoon picnic or tea party. I can see Charlotte York in this dress, strolling down the Manhattan streets.

Éduoard Manet, Vase of White Lilacs and Roses (1883): While Van Gogh, Monet, and Kryushyn opted to paint lilacs in their natural, outdoor setting, on vast, flowering bushes, Manet plucked a few stems and brought them indoors, where they repose with a few roses. Manet has another painting, from a year earlier, in which white lilacs perform a solo act, spreading their frothy, frilly limbs beyond the canvas's limited frame, as if they just can’t be contained.

Three Things I’m in Love With This Week

Cheney Chan’s Fall 2024 “Dream in Bloom” collection: Cheney Chan is a Chinese fashion designer who made his Paris Fashion Week debut in June 2024. His sculptural designs are inspired by nature, especially flowers, and China’s rich history of porcelain-making. The dresses here bloom in 3D, refusing to be flattened, their architectural curves moving fluidly through space.

Cheney Chan Fall 2024 The Arnold Arboretum: Now that the weather is warming up here, my husband and I have been spending our weekends at the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard’s “museum of trees,” where we wandered under cherry blossoms of all sorts and species, wound our way through the Chinese Path, climbed Bussey Hill and Peters Hill, and admired rhododendrons, paperbark maples, the coral embers willow and the rock cotoneaster, and lots and lots of cheerful yellow forsythia. Fittingly, Lilac Sunday is coming up, the one day where you can picnic in this beautiful landscape—while gazing upon the lovely lilacs.

“Lilac, the Color of Half Mourning, Doomed Hotels, and Fashionable Feelings” by Katy Kelleher in The Paris Review: In this column, Kelleher dives into lilac as a color, giving a more in-depth version of The Purple Hotel story and tracing lilac through its more contemporary associations in fashion and interior design.

Words of Wisdom

—O remember In your narrowing dark hours That more things move Than blood in the heart.

—Louise Bogan

A couple of weeks ago, I went to a bookstore with my friend and happened to find a copy of The Blue Estuaries, which collects five collections of Louise Bogan’s poems, as well as her uncollected poems. Born in Maine in 1897, Louise Bogan attended Boston University for a year, dropped out, married, was widowed after two years, married again, and left her husband in the 1920s, moving to New York, where she published her first collection of poems. There she met and mingled with the poets of the day, like William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore, but her own verse swam against Modernist currents, embracing rhyme, meter, and formalism. After publishing her second collection, she became a poetry editor for The New Yorker, subtly shaping America’s poetic landscape for the next 38 years.

Her own poems often deal with themes of love, betrayal, loneliness, and grief (Bogan suffered bouts of depression, for which she was occasionally hospitalized). However, unlike the confessional poets of the 1960s, Bogan was intensely private, and you can sense a reticence to her poems, under which lingers an intensity of emotion and depth of thought that she disciplines into sparse, careful lyrics. The verses here are from “Night,” one of my favorite poems of hers, where one sentence, spread over three stanzas, breaks off before completion, swinging from precise observation of the natural world to the inner world of “the heart,” exhorting the reader directly.

Poetry Corner

Lilac Sonnet

Lilac, the fourfold petalled flower, pale— in the famed dooryard, pale and yet not frail, unfazed by early mist and April rain, fragrant and small and clustered there, with curled slippers of Persian purple, an old-world Ottoman immigrant in a Boston lane. Old-fashioned, curiously so, they linger with matching hats and gloves of lilac finger, old teatime ladies—sipping, biscuiting, and swapping gossip in the shade. The towers of Syringa-sprays, the gentle mauvish showers, the colored wood, the lovely white moth flitting on the thick profusion of a blooming bush, the heart-shaped leaves—it’s true. I love all these.

I wrote this sonnet after I went for a walk and saw several beautiful (and beautiful smelling) lilac bushes. I always feel a little apprehensive about sharing my own poems here, but what can be a better inducement to improve myself as a writer than to know that eyes other than my own will see that writing? The “famed dooryard” is a reference to what must be the most famous poem about lilacs, Walt Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” “Syringa” is the taxonomic name for the lilac, but it also reminds me of John Ashbery’s poem of the same name. Ashbery’s poem is about Orpheus and Eurydice, about the limits of song and song’s ability to stellify the poet, but I can’t help it. The lilac makes me break out into sonnet.

Beauty Tip

Press some flowers! Spring is so short, but pressing its pretty blossoms allows the season to linger a little longer.

Lingering Question

What deeper emotions is your anger masking?

Dear Readers, I hope you are enjoy the first days of May! If this post gave you beauty, happiness, or pleasure, please share with a friend, subscribe to Soul-Making, and leave a like. And I always, always love hearing your thoughts in the comments!

Beautiful post - what’s not to love about lilacs?

"Lilac in me because I am New England,

Because my roots are in it"

Growing up in the greater Boston area, we had lilacs growing in our front yard. Opening the windows on a warm Spring day brought a rush of their fragrance through the whole house, enhanced by cuttings in a big brass pot.

Returning to Boston after grad school, visiting the lilacs at the Arnold Arboretum in May became a tradition. Glad you have discovered the joys of that magical place which many natives are shockingly unaware of.

Congrats on your lilac sonnet, Ramya. Well crafted! 👏