Friday Frivolity no. 31: And damned if I look back

The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice across the ages

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

And damned if I look back1

Tum quoque marmorea caput a cervice revulsum gurgite cum medio portans (Eagrius Hebrus) volveret, “Eurydicen” vox ipsa et frigida lingua “Ah miseram Eurydicen!” anima fugiente vocabat: “Eurydicen” toto referebant flumine ripae.

—Virgil, Georgics IV2

(quid enim nisi se quereretur amatam?)3

—Ovid, Metamorphoses X

There lived a poet once whose song lulled the lioness to sleep and tamed the terrible tiger, whose song hypnotized the birds out of their nests and distracted the butterfly from her flower, whose song made mountains weep in streams and trees spring up as easily as weeds, whose song charmed the deer to dance and the bears to prance, whose song bid fish to fly in underwater flocks or tread water calmly at his feet, listening to him while he sat on the riverbank and plucked his lyre, for “Orfeo mest of ani thing / Lovede the gle of harping.”4

For his song, fruit ripened, wheat swayed in full-grown ears, and meat practically cooked itself. One day, as he was wandering in the woods, this best of poets met the most beautiful of nymphs. Her name was Eurydice. They married—one of those small, rustic affairs, where everything is made lovelier by its simplicity. All the birds and the beasts, the trees and flowers and stones and streams, reveled in jubilation. The bride and the groom were very happy. Eurydice danced in the woods with her friends. Then came the snake. With one bite on the ankle, she fell down dead. No grief could be greater than Orpheus’s then, no song more sad than his lament. But why not go to the Underworld and sing it there? So he made the long journey, down into that realm of shadows from which few return, and pleaded his case to the lord of the dead. Hades would give him back his wife, but on one condition: he must not look back at her as he led her into the world above.

It should have been easy, but as the interminable path continued and the silence wore on and the minutes dripped like water from stalactites in that dim, dark place, he began to doubt that she was really following him. After all, her ghostly footsteps made no sound, her ghostly hand in his had no feel. He turned around. In an instant, she caught his eye and was gone.

“Regrets are always late, too late!”5 but nevertheless he wept. He himself became a shade, a thing of nothing. The woods that they had walked together, the flowers that he had loved to pick for her, the birdsong that they used to delight in, what meaning had they for him now? So it was a relief, really, when the Maenads tore him up and sent his head and his lyre down the river, where the song continued singing, singing of its own accord, singing out to Eurydice, whom it would soon join, a river flowing back to its source, which finally opened to receive it.6

Somehow this moment from Alexander McQueen’s F/W 2006 collection always seems to me to be the moment when Orpheus looks back at Eurydice and he loses her a second time. And both make me think of Milton’s “Methought I saw my late espoused saint.”

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Orpheus Leading Eurydice from the Underworld (1861): I wanted to begin and end the mood board with these two parallel paintings by Corot of Orpheus and Eurydice. In the first, Orpheus leads Eurydice out of the Underworld. They are still in the Underworld—note the ghostly subtleties of the hues, the dreamlike vagueness of the place, the almost shadowy leafiness of the trees, the nebulous huddles of the shades of the dead and their dim, formless reflections. Orpheus holds Eurydice firmly by the wrist, spirit of the dead though she is, leading confidently, his arms strong and muscular, his bearing proud, his head crowned with the laurel wreath that marks him first among poets, his lyre—chief weapon of persuasion—brandished before him like a sword or guiding lantern. Eurydice, meanwhile, is specter-pale and veiled, chaste and bridal.

Frederic Leighton, Orpheus and Eurydice (1864): This Eurydice is bolder, with no small persuasive powers of her own. Unlike Orpheus, she needs no lyre—her gaze is all. Orpheus desperately turns away, desperately keeps his eyes closed, desperately holds back the loving, entreating, wifely embrace he so wants to return. Leighton’s painting was the inspiration for Robert Browning’s wonderful short poem “Eurydice to Orpheus,” where Eurydice exhorts, “no past is mine, no future: look at me!”

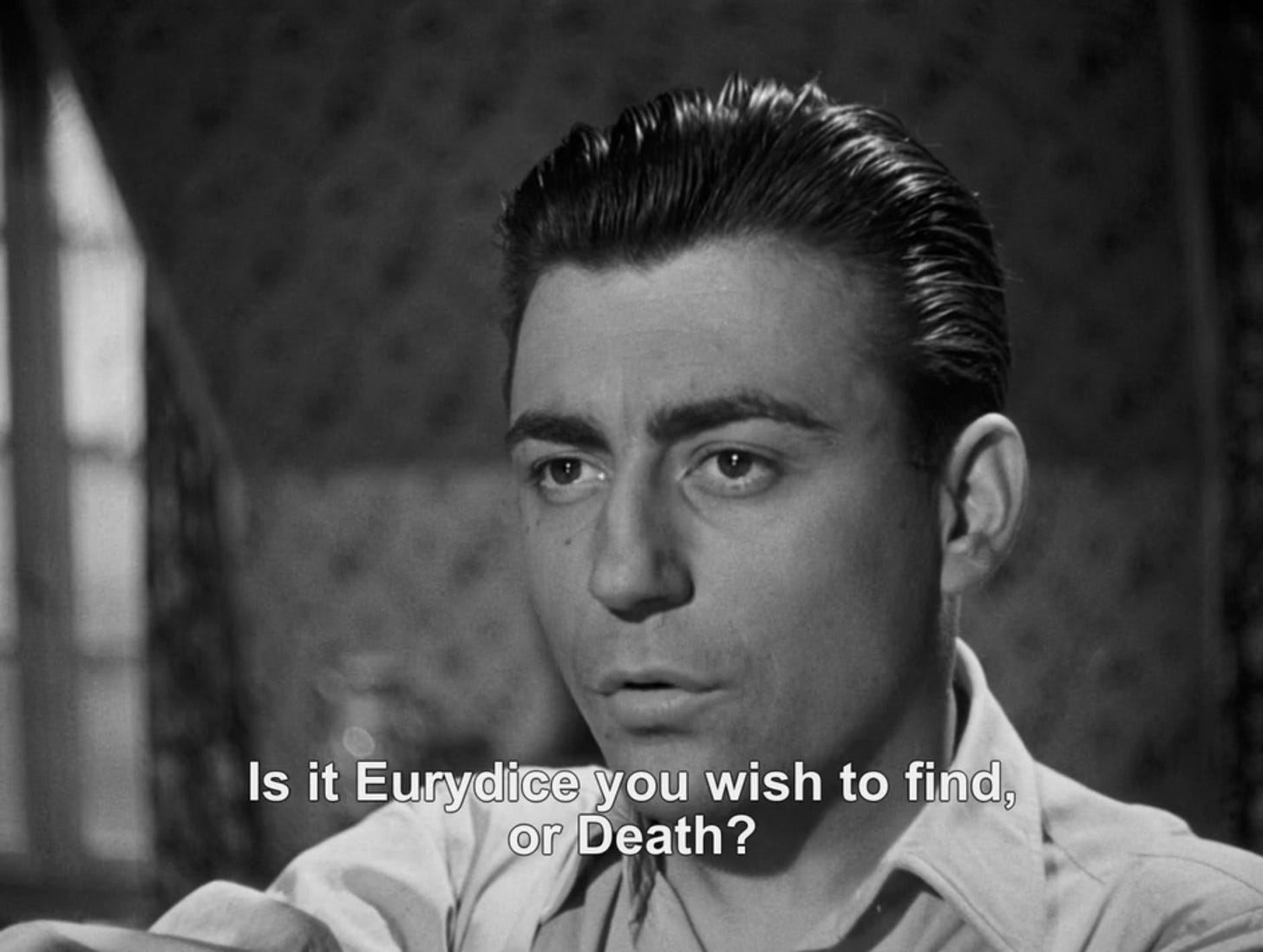

Jean Cocteau’s Orphic Trilogy: Artist, designer, poet, playwright, novelist, and film director Jean Cocteau marshaled his considerable talents towards the making of three films—The Blood of a Poet (1932); Orpheus (1950); Testament of Orpheus (1960)—that use the Orpheus myth as an entry point into a meditation on poetry and the poet. After all, Cocteau referred to novel-writing as poésie de roman, theater as poésie de théâtre, movie-making as poésie cinématographique. Using rich, almost surrealist symbolism, the films serve as dreamy investigations into art, life, death, immortality, the unconscious, and the nature of artistic creation. In the final film, Cocteau himself steps into the frame and plays Orpheus, the eternal poet.

Cast of three-figured relief depicting Hermes, Eurydice, and Orpheus from Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli: This 18th century cast, made from a Roman marble panel which itself was a copy of a Greek original from the 5th century BC, shows Orpheus, on the right, in the fateful moment of turning back to look at his wife Eurydice. There is great pathos in the mutual gaze of husband and wife here, in the placement of the hands—Eurydice rests a hand on Orpheus’ shoulder, as though clinging to him or reassuring him for his renewed loss of her, a hand he lightly touches with his own in a tender gesture, his lyre in his other hand. Hermes, the messenger god, who guides the souls of the dead to the Underworld, stands behind the couple. His fingers already grasp Eurydice’s wrist, ready to take her back to the realm of ghosts. I love the detail too of Eurydice’s veil, which the relief opens up to us the viewers. Was it Orpheus who pushed aside the veil to see her? Or did she open it herself, wanting equally to look at her husband?

Black Orpheus (1959): Marcel Camus set the Orpheus myth in late-1950s Rio, during Carnaval. Breno Mello and Marpessa Dawn make a beautiful couple, Orpheus a singer, guitar-player, and dancer, Eurydice a country girl fleeing the personified figure of Death. The setting of Carnaval is a beautiful chaos of color and song, rhythm and dance. Many Brazilians were disappointed with the film, which they saw as a French, exoticized view of their culture, ignoring the reality of life in a favela. Yet, years after first viewing it, I’m still haunted by the three songs “A Felicidade,” “Manhã de Carnaval,” and “Samba de Orfeu,” which brought bossa nova to a global audience.

Black Orpheus (1959) You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet! (Vous n’avez encore rien vu) (2012): In Alain Resnais’s penultimate film, a group of actors gather to put on the play “Eurydice” by the celebrated, recently deceased playwright Antoine d’Anthac. d’Anthac is a fiction, really a character from a play by Jean Anouilh, the actual creator, too, of “Eurydice.” So many layers of adaptation here: a myth within a play within a movie. The film derives much of its poignancy from its meditations on aging, as older actors vie with younger and performers look back on the Eurydices of their own pasts.

John William Waterhouse, Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus (1900): According to Pausanias, after failing to bring Eurydice back from the Underworld, Orpheus shunned the love of women and turned to men. Angry, the Maenads—female followers of Dionysus—tore him to shreds, and his head floated down the river, still singing, some say, as it went. In Waterhouse’s painting, two nymphs find Orpheus’s lovely head—his still youthful, well-formed face, his long, lush locks, and even his lyre, around which his hair is entangled.

The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, directed by Gia Coppola and produced for Vogue with Gucci (2016): In this high-fashion update of the myth, Orpheus and Eurydice are (Alessandro Michele-era) Gucci-clad, artsy urbanites, Eurydice (Lou Doillon) wearing on her wedding day a glittery pink veil adorned with butterflies and a pink dress snaked with serpents, her wedding ring simply overkill for her already heavily beringed fingers, Orpheus (Marcel Castenmiller) one of those sensitive hipster types, playing in the place of a lyre an electric guitar. Gia Coppola’s dreamy, stylized adaptation preserves the beating heart of the myth while bringing it into the modern world. Central Park stands in for a pastoral setting, the snake is a woman (Vittoria Ceretti) dressed in deadly red, and the Underworld is a nightclub, awash in neon light, with a mysterious ouroboros logo. Orpheus looks back at his wife on a crowded, sunny Manhattan street, she disappears, and the people walk on by, oblivious of his tragedy.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Orpheus Lamenting Eurydice (ca. 1861-5): This painting parallels the first painting, also by Corot, in the mood board. Having failed to bring his wife back to the world of the living, Orpheus laments. The world above looks so much like the world below: trees, grass, and river, with Orpheus occupying almost exactly the same spot on the canvas. But here things are reversed: Orpheus himself, haunted by Eurydice’s conspicuous absence, is now a shade standing on the banks of a river, while the others, reading and conversing, are engaged in the warm tasks of living and hardly seem to notice him.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Orpheus Leading Eurydice from the Underworld and Orpheus Lamenting Eurydice

Three Things I’m in Love With This Week

Sarah Ruhl, Eurydice (2003): Sarah Ruhl lost her father at the age of 20, and her play Eurydice, which is dedicated to him, makes its most significant relationship not that between husband and wife but between father and daughter—even “[a] wedding is for daughters and fathers…. They stop being married to each other on that day.” Eurydice’s father is also dead, and when she dies, she meets him again. Unable to bear leaving him, she deliberately walks up to Orpheus and calls his name, with the inevitable result that he turns around, looks at her, and she dies all over again and goes back to the Underworld. Having lost my father in the past year, I can relate. I’d give anything to sit in a string room with him as he teaches me how to read.7

Christoph Willibald Gluck, Orfeo ed Euridice (1762): The earliest surviving opera is Jacopo Peri’s Eurydice, but my favorite Orpheus and Eurydice opera is Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice. In this version of the myth, Orpheus doesn’t explain to Eurydice the injunction that he can’t look at her as he leads her out of the Underworld. Hurt and confused by this, thinking it a sign of waning love, Eurydice movingly sings her grief to her husband. He can’t help it: he turns around. But Gluck gives us a happy ending, courtesy of Amore, who just wants to see the two lovers reunited.

Original Hadestown album by Anaïs Mitchell (2010): Before Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown became a big Broadway musical, it was a humbler concept album, for which Mitchell recruited her singer friends, like Justin Vernon (Bon Iver) and Ani DiFranco, to play the parts of Orpheus and Hermes, Persephone and Hades and The Fates. As for Mitchell herself, she was Eurydice. I used to listen to the album again and again as a teenager—and how could I help it? “Way Down Hadestown” is just too catchy:

Words of Wisdom

Failure

We are much bound to them that do succeed; But, in a more pathetic sense, are bound To such as fail. They all our loss expound; They comfort us for work that will not speed, And life—itself a failure. Ay, his deed, Sweetest in story, who the dusk profound Of Hades flooded with entrancing sound, Music’s own tears, was failure. Doth it read Therefore the worst? Ah no! So much to dare, He fronts the regnant Darkness on its throne.— So much to do; impetuous even there, He pours out love’s disconsolate sweet moan— He wins; but few for that his deed recall; Its power is in the look which costs him all.

—Jean Ingelow

Jean Ingelow was a Victorian writer who first became popular for her poems, though she also wrote novels, short stories, and children’s books. One of these children’s books was Mopsa tbe Fairy, which centers around a boy named Jack, who ends up in fairyland and meets the fairy child Mopsa. For the epigraph of the last chapter, Ingelow uses her own sonnet, and it is a poem that cuts right to the heart of the myth in a way that I’ve seen few other works do, only needing fourteen very concise, tightly written lines to do so.

I first discovered this poem in John Hollander’s The Work of Poetry (1997). I had never heard of Ingelow, and indeed Hollander dismisses much of her verse as slight, trifling, typical Victorian fare. But somehow, here, putting on the persona of Jack, Ingelow “could recover a Keatsian power” to produce what Hollander calls “one of the finest short poems of its time” and “one of the major lost poems of the nineteenth century.” For Ingelow here, the Orpheus story counterintuitively comforts us about failure. After all, if Orpheus had been successful, the story would never have been so powerful, would never have been remembered so well over the millennia, would never have spawned so many offspring, would never have resulted in wonderful sonnets such as this.

Poetry Corner

Orpheus

I swear by Tanaïs, black river from six urns, And Zeus, who rides upon great chariots as stars burn, Drawn by the bulls of Rhea and by Nyx’s horses, And giants of former times, and men of newer sources, Pluto who devours us, Uranus who makes us be, I love a woman who is sacred unto me. The monster with blue hair, Poseidon, hears me out, And may he grant my wish. I’m the human soul singing out; I love. The dark immensity is full of clouds, The heavy rain abounds with leaves in whirling crowds, And Boreas moves the woods and Zephyr moves the wheat, And in this way, profoundly, love disturbs our heart-beat. I’ll love this woman named Eurydice Always, past all! But if I fail, let heaven curse me, And let it curse the nascent flower and the wheat-ear’s all. You there—do not trace magic words upon the wall.

—Victor Hugo, translated by me8

The 12-syllable alexandrine is to French poetry what iambic pentameter is to English. Here I have kept, as much as I could, the alexandrine, which in English is iambic, and also preserved the rhyme scheme of rhyming couplets. In this poem we see Orpheus not in the role of poet or artist but as devout, devoted husband and lover of Eurydice. In the French, there is a through line from j’atteste to j’adore une femme to j’aime to j’aimerai… toujours. I also like the assonance between je suis l’âme and j’aime, as though loving Eurydice is somehow connected with his being “the human soul singing,” a part of his fundamental identity. If he fails in this love, the “magic words” go, too.

Beauty Tip

Keep your eye on the road—one cannot drive looking continually in the rearview mirror.

Lingering Question

Why do you think Orpheus turned to look back at Eurydice? Was it out of love for her? Because she wanted him to? Because he doubted that she was following?

Dear Readers, this post was very long and involved, probably because I am currently working on a poetry collection inspired by the Orpheus and Eurydice myth, but I hope you enjoyed! If you did, please share this post with a friend, subscribe to Soul-Making, and leave a like. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

Translation by A. S. Kline:

Even then, when Oeagrian Hebros rolled the head onwards, torn from its marble neck, carrying it mid-stream, the voice alone, the ice-cold tongue, with ebbing breath, cried out: ‘Eurydice, ah poor Eurydice!’ ‘Eurydice’ the riverbanks echoed, all along the stream.

(for what could she complain of except that she’d been loved?)

John Ashbery, “Syringa.”

c.f. Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, translated by Edward Snow:

But when, in which of all these lives, are we finally open and receivers?

In 2020, Ruhl’s play was turned into an opera by Matthew Aucoin, with a libretto by Ruhl. Here’s a bit of it, performed at The Met by Erin Morley.

The original French:

J’atteste Tanaїs, le noir fleuve aux six urnes,

Et Zeus qui fait traîner sur les grands chars nocturnes

Rhéa par des taureaux et Nyx par des chevaux,

Et les anciens géants et les hommes nouveaux,

Pluton qui nous dévore, Uranus qui nous crée,

Que j’adore une femme et qu’elle m’est sacrée.

Le monstre aux cheveux bleus, Poséidon, m’entend;

Qu’il m’exauce. Je suis l’âme humaine chantant,

Et j’aime. L’ombre immense est pleine de nuées,

La large pluie abonde aux feuilles remuées,

Borée émeut les bois, Zéphyre émeut les blés,

Ainsi nos coeurs profonds sont par l’amour troublés.

J’aimerai cette femme appelée Eurydice,

Toujours, partout! Sinon que le ciel me maudisse,

Et maudisse la fleur naissante et l’épi mûr!

Ne tracez pas de mots magiques sur le mur.

The English poet Algernon Charles Swinburne wrote a sonnet in reply, called “Eurydice—To Victor Hugo,” which tells Eurydice’s side of the story:

Orpheus, the night is full of tears and cries,

And hardly for the storm and ruin shed

Can even thine eyes be certain of her head

Who never passed out of thy spirit's eyes,

But stood and shone before them in such wise

As when with love her lips and hands were fed,

And with mute mouth out of the dusty dead

Strove to make answer when thou bad'st her rise.

Yet viper-stricken must her lifeblood feel

The fang that stung her sleeping, the foul germ

Even when she wakes of hell's most poisonous worm,

Though now it writhe beneath her wounded heel.

Turn yet, she will not fade nor fly from thee;

Wait, and see hell yield up Eurydice.

As my husband is driving us through the UsS I took the time to read your wonderful analysis of this myth. I a . amazed at your in depth a description of each picture you took the time to find. I love your writings.

Such a great compilation of Orpheus and Eurydice throughout history 🤍 curious, did you watch Kaos last year? It's a series that also covered the myth, but in a different way. I'm sure you'd enjoy it!