This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

Cool Heart

No more hysterics, no more melodrama. No more loudness, no more screaming. No more thunder, no more bursts. No more fits, no more paroxysms. No more emotions veering from extreme to extreme, from peak to peak, from high to low, going up and down, ricocheting, leaping, vaunting, plunging, erupting. Now one longs for a cool hand, a hushed voice, stillness, a little breeze stirring the curtain with its gentle breath. Now evening comes over the garden, and the flowers bend their heads, and the mice scurry back to their holes to be cozy, and the grass murmurs a little over the ground, and the fountain slows to a trickle. There is no need for fortissimos any more, just a simple rustle of melody, a shimmer on the surface, “a spell of rest, and quiet breath, and cool / heart.”

Art depends on cymbal-crashes of emotion, can’t live without them. Otherwise we would be terribly bored, we would find no point in dwelling in that other world, that created world which is not our own, and we would take the artist up for fraud. But life cannot always be lived at such a fever-pitch, and I think our most productive hours are spent—our best work is created—in an air of serenity and peace, in an attitude of reflection, stillness, fertile silence. Let silence not be death but life—let there be silence that means the quiet hum of thought, a hushed awe in the face of sublime art or nature. Let silence be the space between action and reaction, between our lowest and our highest selves, between what is automatic and what is intentional. Silence means carefulness, control, precision—the hand of the artist hovering above the paper, drawing something in the mind first, before the tip of the pencil makes a mark on the page and either mars it or sets it off on a course of greatness.

Writing itself is more an act of listening than of talking. Talking is always surfaces, but listening is the bedrock of conversation. Listening goes deep into the root of things, reaches that darkness where the seed sprouts and the friendly worm trudges, where life exists in its pulsing, throbbing, humming verve, and an uncertain chaos yields to a form that is continually in the process of defining itself. Where do the words come from? My surface self, my talking self is so banal—it has no wit, no ability to piece things together, no lightning flashes, but my writing self coaxes phrases and sentences seemingly out of thin air, out of some dim recess or cellar or attic of my brain, out of some primeval sludge of consciousness that must be shared by us all and, I suspect, links us to God.

I don’t want to skate on surfaces, I want to pierce through, fall, sink ever downwards to the center of the earth, letting the water cover me, rush past my ears as I descend slowly, slowly, the way a stone descends to the riverbed. There is always a deeper knowledge, a more profound truth. Who knows how far down the center goes, how many layers one has to cross to arrive there? Is it possible to make our silences all the more silent, all the more soundless, all the more hushed and reverential, and yet more ripe with meaning, more blooming and more fecund, more alive than—all of this?

Let the world go to hell, I say, but I must always have my peace and quiet.

Mood Board of the Week

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Justine Kurland, The Family (2002): I remember coming across Justine Kurland’s photographs of teenage girls on Tumblr when I myself was a teenage girl and identifying with these images of disaffected youth, idle adolescence. At the age of 15, Kurland ran away from home to an aunt in Manhattan, and she writes that she “employed the trope of the teenage runaway as a shortcut to freeing [teenage girls] from the cage of their suburban bedrooms and bringing them into a world of their own making.” In the ’90s and early 2000s, she went on road trips across the US, finding girls who would collaborate with her in order to create these “girl pictures.” Here Kurland captures an idyllic, almost Edenic scene, where the the water is so clear you can see through to the stones of the riverbed, and summer light hazes in the abundant green.

Justine Kurland, Daisy Chain (2000) and Shipwrecked (2000) American bison by S. Wilson, from Wild, Wild World of Animals: Wild Herds (1977): The American bison, also called the buffalo, is the largest terrestrial animal in North America and once roamed over most of the interior U.S. Today, wild bison are only found in national parks or reserves. Although this picture comes from a book about herds, I like how this bison stands serenely by itself, in a plain of waving grasses, against a big, big sky. I wonder what he or she is thinking about.

Tyler Mitchell, Riverside Scene (2021): Tyler Mitchell (1995—) got his big break at the age of 23 when he shot Beyoncé for the cover of Vogue, but I think the real poetry of his images comes out in his Southern Landscape series, for which he went back to his home state of Georgia, reclaiming places where black people were historically enslaved, subjugated, redlined, or excluded as a utopia in which they are instead visualized as “free, expressive, effortless, and sensitive.”1 Riverside Scene echoes Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-6) in its depiction of people sitting on the banks of a river, enjoying the loveliness of a beautiful day, and it also reminds me a little of Julie Dash’s 1991 Daughters of the Dust.

Max Nonnenbruch, Evening by the Lake (1901): A German painter part of the Munich School, which was known for its naturalistic depictions of landscapes, portraits, genre scenes, and still lifes, Max Nonnenbruch (1857–1922) often painted beautiful young women in a neoclassical style, surrounding them with complex symbolism. I love the serenity of this one in particular, its calm, cool colors and its air of stillness and hush.

Paul Stankard, Cactus flower paperweight (1985): In his books on his creative journey, Paul Stankard (1943—) describes how his dyslexia contributed to his struggles in school and his being labeled a “slow learner.” Nevertheless, he applied himself diligently to learn the art of glass-blowing, first beginning as a scientific glassblower to create lab equipment. After seeing the famous Blaschka glass flowers at Harvard, he was inspired to make paperweights based on flowers and plants.

Paul Stankard paperweights, via Corning Museum of Glass Nils-Udo: Art in Nature (2002): Nils-Udo (1937–) is a German artist who moved away from painting in the 1960s in order to embrace nature itself as a canvas and sticks, petals, branches, and leaves as his “painting” materials. His art heightens our awareness of the beauty and harmony of nature, investigating time, the impermanence of art, and the relationship between humans and our natural environment.

Photograph of Vietnam by Hà Thành: What I love about this photograph are the different layers of color in the sky, from yellow to pink to blue with clouds, setting these terraced hills against a dreamlike backdrop.

Celebrity Homes II, edited by Paige Rense (1981): This veranda comes from The Cedars, the home of actor George Hamilton, in Mississippi. Built on a plantation, the house was expanded when the first owner’s bride-to-be told him, “I cannot marry you unless you give me a house with more style.” Hamilton, with the help of Hollywood set designer friends, worked on restoring the house, attempting to capture the style of period while modernizing where necessary (e.g. adding air conditioning). The restoration was not without its hindrances, as Hamilton describes: “The verandas run the width of the house, and everyone loves to sit outside. In fact, several days ago I was sitting outside thinking that the house was all finished—when a sudden splash of honey came down, and I realized the bees had bored into the rafters again. But that’s part of living in the South.”

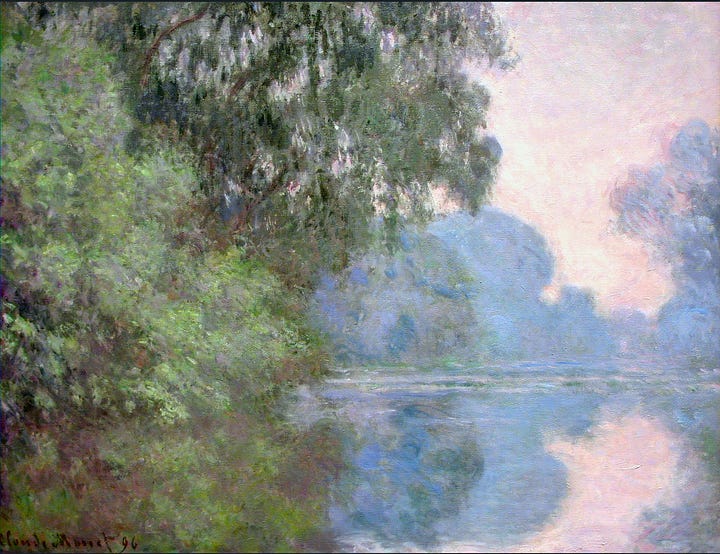

The Cedars, from Celebrity Homes II (1981) Claude Monet, Morning on the Seine, near Giverny (1897): I love how Monet will painting the same subject over and over again, on different days and during different times of day, in order to capture subtle variations of light and color and mood. Monet had moved to the village of Giverny in 1883 and lived there for over 40 years, until his death. In the summers of 1896 and 1897, he would wake up early, around 3:30, and wait for the sunrise. Often starting on a bateau-atelier, or boat-studio, he would finish the paintings on land, capturing the place where the Epte met the Seine in a series of about 20 paintings.

other versions of Morning on the Seine, near Giverny, via WikiArt

3 Things I’m in Love With This Week

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot: Everyone is reading Middlemarch apparently, but I’m about halfway through this other absolute doorstop of a novel by George Eliot, and it is wonderful. Eliot is so sharp and so good at creating and capturing characters. Gwendolen Harleth, a self-involved, attractive, spoiled woman in her early 20s, whom we first meet at a roulette table in a serpentine dress, is one of these characters, and probably the most compelling—not just in the world of Daniel Deronda but of the library of literary heroines that live in my brain.

Eva Oertli and Beat Huber, The Hand (2004): This sculpture of a hand in Glaurus, Switzerland, sometimes called The Caring Hand, surrounds a tree, creating the impression that the tree is growing out of the hand, that the hand is creating the tree. “With our sculpture we do not want to set a monument to the gardening profession, but rather point out that we, as a great human race, are responsible for our living space,” the sculptors said.

Lace Fences: Anne Eunson is a lace knitter who decided to knit her own fence, using twine, as well as modified curtain rods as knitting needles. Living in Shetland, Scotland, she drew on that place’s rich tradition of knitwear and knitting, and she actually sells the pattern for her fence here, just in case you ever wanted to knit your own! A group of Dutch designers called De Makers Van has also created lace fences, uniting the hostile, tough, industrial chain-link fence with the artistic, delicate, handcrafted tradition of knitting to lend urban spaces a unique beauty.

by Anne Eunson Designs / Lace fence designed by De Makers Van, via Redfort Architectural Fabrics

Words of Wisdom

I hear stories about directors who scream at actors, or they trick them somehow to get a performance. And there are some people who try to run the whole business on fear. But I think this is such a joke—it’s pathetic and stupid at the same time.

When people are in fear, they don’t want to go to work. So many people today have that feeling. Then the fear starts turning into hate, and they begin to hate going to work. Then the hate can turn into anger and people can become angry at their boss and their work.

If I ran my set with fear, I would get 1 percent, not 100 percent, of what I get. And there would be no fun in going down the road together. And it should be fun. In work and in life, we’re all supposed to get along. We’re supposed to have so much fun, like puppy dogs with our tails wagging. it’s supposed to be great living; it’s supposed to be fantastic.

— David Lynch, Catching the Big Fish

David Lynch died on January 15th, and up till that point I had only seen Blue Velvet (1986) and bits and pieces of Twin Peaks. In the past week, however, I watched Mulholland Drive (2001), which at first I was confused by and then—after watching a 20-minute video about it on YouTube—loved and was moved by (many such cases). In Catching the Big Fish, Lynch writes about creativity, the artistic process, making movies, and his experiences with meditation. Here he talks about the importance of creating an environment of calmness, joy, love, and fun, and how that allows people to work better and to live better—because it is “supposed to be great living.”

Poetry Corner

The Work of Happiness

—May Sarton

I always mix up May Sarton (1912–95) with May Swenson (1913–1989), and though on the whole I prefer Swenson, I love this poem by Sarton, which describes happiness as the work of “the peace of hours,” a product of “inwardness,” where life slows down and even “the walls are kind.” As I grow older, I find myself less and less associating happiness with a riotous firework display of joy and more and more with quiet contentment, stillness, gentle tenderness.

Beauty Tip

Add something to your living space that brings you a sense of peace and serenity whenever you look at it.

Lingering Question

Do you find that you’re more productive when you have peace and quiet, or are you the sort of person who likes to always have a little something in the background?

Dear Readers, how have your Januaries been? I hope you enjoyed this post—please like it and share with a friend if you did, subscribe to Soul-Making for more, and let me know your thoughts in the comments, as I always look forward to hearing from you. Have a wonderful weekend!

Tyler Mitchell, I Can Make You Feel Good (2020).

I love how you so eloquently describe the link between calm and creativity. The Paul Stankard pieces look beautiful too - like nature frozen in time.

I definitely need peace and quiet for productivity. When I work from home, I play ambient instrumental music in the background because even lyrics distract me. At old jobs, I've had coworkers who were very surprised at how much time I wanted to spend alone lol. Great roundup as always, Ramya 💞