Don't Turn Your Back on Me, Baby

In the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich and Matthew Wong, art turns its back on us—and invites us in.

It is bad etiquette to turn your back on someone; after all, art is a conversation. Look at a portrait, and you are looked back at, as seen as you are seeing. The gaze is mutual, relation is embedded in it. And how important the subjects’ faces are, open to you as a book is open. How the artist has labored and exerted all the power of his craft to convey a certain set of the mouth, a peculiar faraway look in the eyes, a fine furrowing of the forehead like creased linen, all the subtleties that make physiognomy speak personality. Even when the figures are placed at an angle, you can still read something in them, you can still catch a glimpse of a human face, you are still permitted to know this person and to comprehend them as an individual, a unique being, a subject.

With the Rückenfigur, however, the compositional device that in German literally means “back figure,” the subject turns his back on us; his gaze is redirected to the world he’s been painted into. Why, after all, should he also not be permitted to look upon the scene that the painter has slogged to create? Why should that only be the viewer’s privilege, why shouldn’t he and we gaze at the same thing? But with this turning away, we are denied him. What we get instead is only the subject’s body from the posterior plane; turned away, he becomes anonymous, unknowable, incognito. What he is thinking or feeling we don’t know, are not permitted to see. Neither—for who can be sure that the people in paintings don’t think or feel or even, when we’re not looking, whisper to each other about us—does he see us. We could be making fun of him, making faces at him, sticking our tongue out at him, coming at him with a knife to slash the delicate canvas, and he would never know it. Indeed, stealing a Rückenfigur painting might be easier on the conscience—no one looks down at you from the frame as you make off with it, painted eyes full of reproach and accusation. How difficult it is to do what is right when no one is watching! What mischief can be gotten up to when backs are turned!

For when we see a person from the back, we are seeing a side of her she could never see herself. Swivel her head on her neck as she might, turn it this way and that way, nature limits her from pivoting 180º and surveying the full prospect of her posterior view. It is a view only others see fully; whether something is stuck to the back of our shirt or our hair is in a bad state or our buttocks wobble precipitously as we walk remains—unless someone were to kindly inform us—sadly unknown. We walk facing forwards; our faces and our fronts greet the world first, and our backs pursue us like shadows, always following, never leading. “My mother forbad us to walk backwards,” Anne Carson tells us in one of her short talks. “That is how the dead walk, she would say.”1 Carson makes a correction to this superstition, which she says her mother must have gotten from a bad translation: the dead “walk behind us,” not backwards. But I believe her mother, for somehow the image of the dead walking backwards has remained with me. Why wouldn’t it make sense for ghosts to trek backwards through their lives, trace their way backwards from the point marked “death” to the point marked “birth,” along the route picking up the thread of their lives, reliving a thousand times over what has already passed and can never come again? The dead walk backwards because time only moves forwards. According to physicists, time moves slower the faster one moves through space—by that logic, why shouldn’t moving backwards through space move a ghost backwards through time? But I digress.

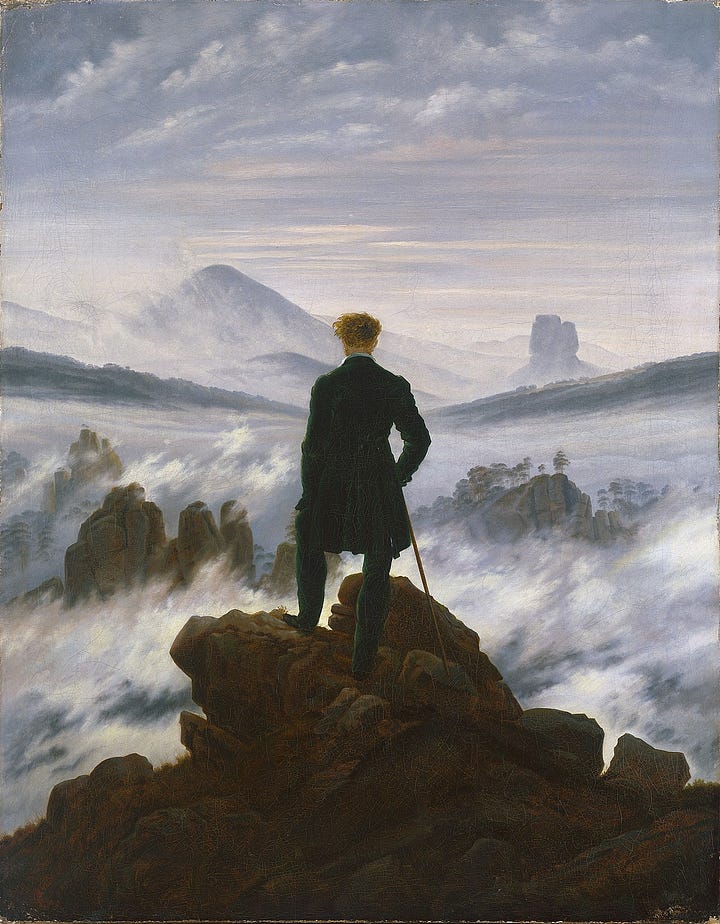

Let’s consider Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), perhaps the most recognizable example of the Rückenfigur in the history of art. A man stands alone on a crag, his back to us, surveying a scene of almost impenetrable fog. Fog rolls off mountains; rocks rise out of the mist in vague insinuations. The brown of jutting cliffs becomes a deep gray robed in lighter gray, until the mountains are nearly the same color as the sky. The wanderer, dressed in a dark green frock coat and dark green trousers, his legs slightly apart, one knee bent over the precipice, a walking stick in his right hand, seems to have arrived here after a long, hard climb. His triumph is palpable. Commanding in stance, imposing in posture, contemplative in attitude, he stands over the world “like the God of creation,” and isn’t looking, after all, a kind of creation?2 “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; / I lift my lids and all is born again,” goes a poem by Sylvia Plath, a more humble theory of relativity than Einstein’s, to be sure, and yet one you can prove yourself right where you are.

Relativity: the wanderer occupies the center of the painting, the subject supreme, and all the world must be conceived of in relation to him. Were his back not turned to us, were we to see him from the other side, we would become fascinated with his face and his features and his expression, for what is more fascinating to a human being than—barring his own face in the mirror—the face of a fellow human? We would start to read him from top to bottom, first the subtle language of his eyes, his brows, his nose, his mouth, his chin, and then the perhaps less careful characters of his dress and bearing. As we succumb to the urge to interact with what linguist Keith Allan aptly calls “the #interactive side#,” the landscape would fade into the background and become mere backdrop.3

With his back turned to us, however, the wanderer loses this specificity, he is himself befogged, as it were, and as a result we do not interact with him but through him, becoming less interested in him than what he is looking at. You might ask, why not paint a simple landscape, then, why this blank figure inserted into the middle of it, who interrupts nature’s prospect, precluding our sight of what he blocks? It is because, posed like this, we are able to become one with him, to become him. Both the subject and viewer face the same direction, and so I as viewer can achieve a simple mathematical substitution of myself for himself—the art-gazer gains a doorway, and so it is I who perch atop a peak, overlooking a sea of fog. Unable to discern his thoughts and feelings, I must create and substitute my own emotional response. More is demanded of me, of my imagination, my heart, my soul.

In the 1st century AD, the Greek critic Longinus wrote On the Sublime, but it was not until the Romanticism of the late 18th and early 19th century that the sublime found its true and proper artistic expression, that it was recognized as the sparks struck from the encounter between the human soul and the godlike vast beauty of nature.4 As cities became clockworks of wheel and steam, cog and machine, as the “dark Satanic Mills” began rapidly to shut out sky and cloud and tree and bird, to dirty the air and shroud the human spirit in not fog or mist but black, thick smoke, nature became a separate entity, something a person wasn’t already embedded in but something one had to seek out specially, through a walk or hike or trek up the mountains. Nature, then, loomed larger and more strange; it overawed the eye, it flooded the senses, it struck the soul with greater vigor.

Friedrich’s Wanderer is always united in my mind with Keats’s sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.” Here is the sestet:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken; Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men Look’d at each other with a wild surmise— Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

“Watcher,” “ken,” “eagle eyes,” “star’d,” “Look’d”—all words of sight and seeing. But what Keats is describing is the experience of reading, of reading George Chapman’s translations of Homer—fluid, immediate, pulsing translations, not at all like the stilted polish of Alexander Pope, translations that opened up the vista of the Greek classics to the young poet like a “new planet” or what the New World must have been to the conquistadors, overwhelmingly sublime. Now that I come to think of it, I realize I always see these figures—the astronomer, “stout Cortez” and his men—from the back, for it is not the speaker himself who is gazing at the skies, the planet, the Pacific; instead, the speaker gazes at those gazing, gazes through them, for they are Rückenfiguren through whom he is granted access to the skies, the planet, the Pacific.

In fact, it could be said that through the subjective act of their looking, they create the skies, the planet, the Pacific. In an essay on Lord Byron, Northrop Frye writes that the Romantics no longer thought of nature as “a divine artefact… a structure or system presented objectively to man, but rather as a total creative process in which man, the creation of man, and the creation of man’s art, are all involved.”5 As Keats the poet conspires with Chapman the translator in the “total creative process” of sailing upon the verse rhythms of Homer’s Odyssey, so the viewing subject conspires with nature to work together in an act of creation. The Rückenfigur is not just man the individual, man the subject, man the viewer, but man the creator, the artist whose work is on an equal plane with nature. “Touched by the true sublime, your soul is naturally lifted up, she rises to a proud height, is filled with joy and vaunting, as if she had herself created this thing that she had heard,” says Longinus.6

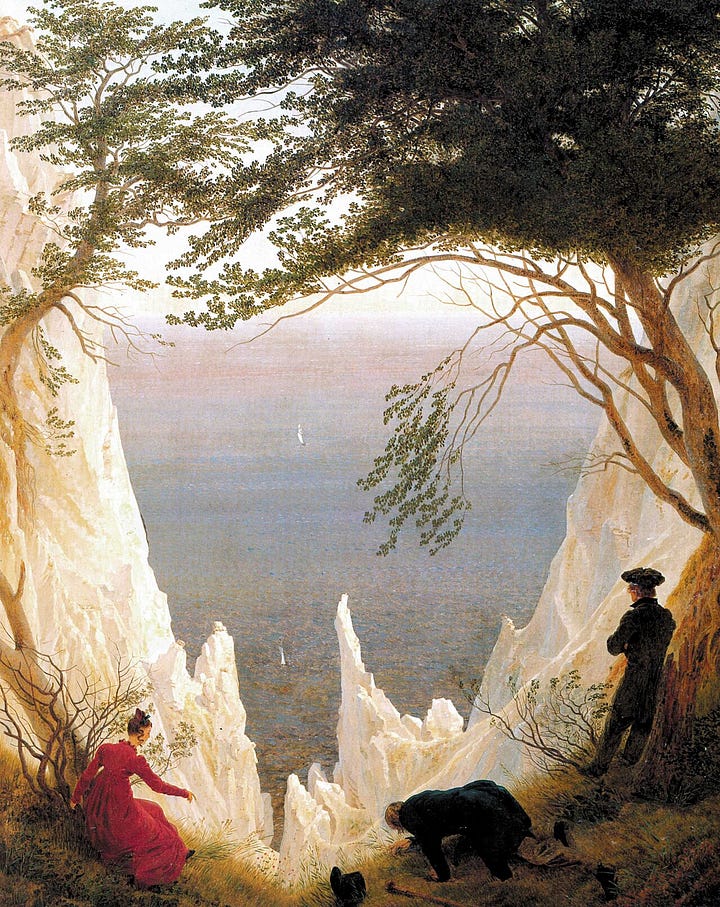

Friedrich was not the first artist to use the Rückenfigur, but before him it was like a technique in search of an artist. “In order not to hate people, I must avoid their company” was one of his few recorded remarks. Several of his paintings are landscapes devoid of people. When people do occur, they turn their backs on the unwashed masses (us) and shut themselves up in their snail-shells of solitude, of spiritual communion with nature. Sometimes they are solitary, sometimes they are grouped with companions. In Woman before the Rising or Setting Sun (ca. 1818-24), a woman in a long dress stands silhouetted in a field. She faces a collection of brown hills and a glowingly orange sky, dusk or dawn, her arms lifted as if in invocation of the sun. In three variations of Two Men Contemplating the Moon, one with an ominously dark landscape, one with a friendlier kind of twilight light, one with a man and a woman, two silhouetted figures bring us into their hush of contemplation, their mystical reading of the divine celestial symbol that is the moon. Both Moonrise Over the Sea (1822) and Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (1818) contain three figures from the back. In the first are two women and a man, in the second two men and one woman. In both the sea is the object of contemplation; in Moonrise it is a dark plane with a dazzle of moonlight resting on it, in Chalk Cliffs a pale wash of blue tinged with rosy sunlit brightness.

Observers rather than observed, the figures both bring us into the scene and create distance between us and the world. We cannot have the world as it is, pure and simple, but are forever doomed to mediate it, contemplate it, interpret it, translate it. We are chained to perception, fettered to subjectivity. As Kant argues in the first critique, we humans can only experience only the realm of appearances, not the realm of things in themselves.7

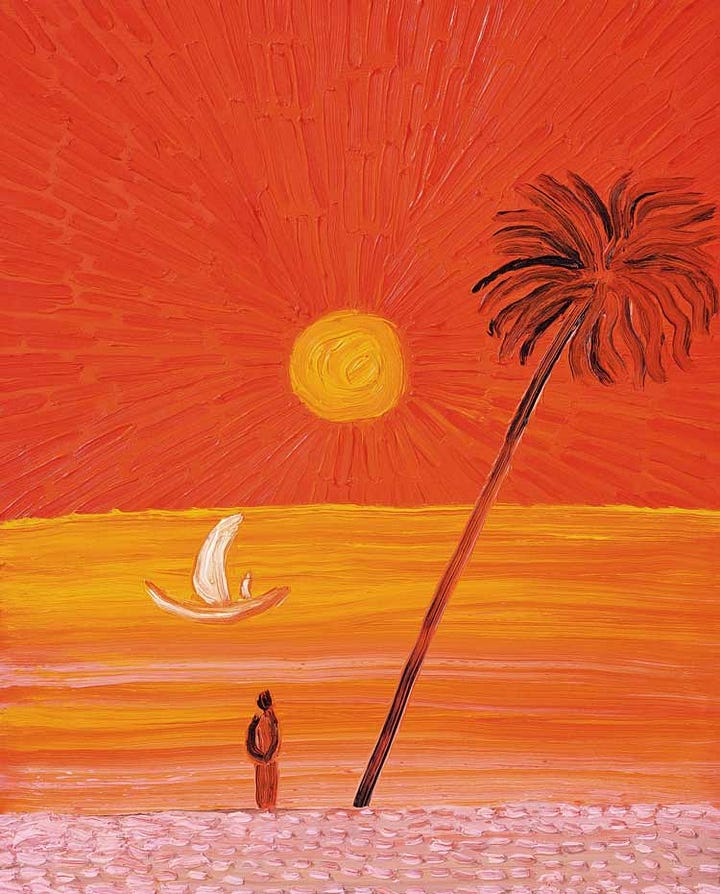

The Realm of Appearances is the name of an exhibition I went to a year and a half ago at the MFA in Boston, centered around the art of Canadian painter Matthew Wong. Wong has a painting called See you on the Other Side (2019), completed almost exactly 200 years after Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. Paintings talk to each other across years and distances, and I could hear Wong’s painting whispering to Wanderer like a distant relation. Parallels abound. Like Wanderer, we have a vast and sublime landscape. Like Wanderer, this landscape is looked upon by a single, solitary subject. Like Wanderer, the subject stands on a cliff, and we see him only from the back.

Stylistically, the two painters could not be further apart. Friedrich came before Impressionism, Wong is clearly post-Impressionist. Friedrich’s hues are usually muted, gloomy, dark, veiled with mists and shadows, while Wong revels in a riot of brightness, an explosion of saturated and variegated color. Friedrich’s paintings are so still, so hushed, that were you to step into one of his landscapes you would be afraid of treading on a twig and breaking the spell, but Wong is movement, pulsations, emanations, flow and rhythm, rendered by visible brush strokes and thick daubs of paint and stipples and specks that are layered in a heavy ferment of life. Yet both painters are Romantics, both produced vast canvases of the natural world, both were devotees of the sublime, both, when they made use of human figures, had those figures turn their backs on us to steep themselves more deeply in that sublime.

In See you on the Other Side, a lone, minuscule figure in blue perches on a brown cliff that slides off the canvas. In the foreground are a red phoenix and a tree where hang a few bare leaves. The figure gazes at a house in the distance, which looks like a child’s drawing of a house: a white rectangle for its body, a brown triangle for roof, a few little blue rectangles for door and windows. Behind it, a green rush sweeps off towards the right, while in the left, above a midnight-blue mass, stars cluster thickly in stipples, embedding almost secretly the slender scimitar of the moon. Between the beholder and what he beholds is a white plain, a vast emptiness. Where Friedrich washed over his scene in swathes of fog, Wong subtracts even further and gives us—museum-goer, look closely now—bare, unpainted canvas, a true void.

What is this inclination towards the void, towards emptiness? In Monk by the Sea (1808-10), a small, black-robed figure stands alone on a shore, staring out into the vastness of the sea and the sky, which occupy most of the canvas. Unlike the wanderer, who stands triumphant over nature, the monk is consumed by it, overawed, subsumed. Friedrich had initially painted two sailboats on the sea, then effaced them with the intense, deep teal of the sea and sky. Aside from this painting, most of Friedrich’s figures are human-sized, not minuscule—clear enough to discern certain features of their dress or hair, even if their fronts are turned away from us. But the monk is so small and so anonymous, hardly a blot on the world, like the seagulls who punctuate the sky like accidental marks, inadvertent commas.

Most of Wong’s figures are like the monk: tiny, anonymous, blank, without detail or definition. Two minute creatures on a beach at sunset, which is abstracted in pure plains of inky brown, blue, and orange; a brushstroke of a figure watching an awesome sun spread its vigorous red-orange rays across the sky, drenching the sea in sunset colors; even—a rare interior, urban scene—a small blonde woman at her balcony, staring across the sea at a city’s lit-up skyscrapers, all the objects in the room larger than her and cut off from the normal rules of perspective so that they appear like symbols floating in a dream.

In fact, all of Wong’s paintings are like dreams; all of his landscapes are landscapes of the imagination. Matters of scale are dealt with loosely; people and houses, sun and moon, trees and leaves reduce to a childlike simplicity; roads are ribbons of paint. The wild rhythms of dots, lines, textures, colors—“all things counter, original, spare, strange”—coalesce into something almost hallucinatory, hypnagogic. No mountain here could be a real mountain, no thicket of trees a slice of real forest. In an interview, Wong said that he lived “a fairly reclusive life” and found “the most stimulation and enjoyment from matters of the mind, be they following the natural path of [his] imagination or watching films in the dark of [his] living room.” These are mindscapes, then, maps of the interior.

As it turns out, Friedrich’s landscapes, for all their naturalistic detail, their precision, their resemblance to real mountains, real cliffs, real seas, real moons—are also mindscapes, imaginary landscapes. He rarely painted straightforwardly what he saw; instead, he would cobble together separate elements from separate moments, separate vistas and scenes, separate geographies, adding and subtracting, editing and splicing until the vision was realized and the landscape stood only a faithful representation of the geography that lay inside the artist himself.

Some artists are interested in accurate representation, some in abstraction, some in color alone, some in form alone, some in geometry, some in anatomy, some in religion, some in mythology. But the Romantic is interested in the soul. The Romantic may collect impressions from the world—and indeed he must—images, shapes, forms, colors and textures and sparks of ideas, but it is always in the “smithy of the soul” that the work is forged and out of which it emerges, like Friedrich’s wanderer or Wong’s blue figure, “silent, upon a peak in Darien.” It is the inner cliffs and valleys, the inner forests and seas, the inner suns and moons that make their way onto the blank expanse of the canvas and prove above all else to the artist a sublime overawing creative power, which is also what we might call God.

The lone Rückenfigur, confronted by the sublime, is always a cipher for the artist, then, who co-creates with nature a specific vision of the world, a vision which is always and necessarily mediated through the subject. Yet in order to “see into the life of things,” as Wordsworth tells us so famously in “Tintern Abbey,” to reach that “sense sublime / Of something far more deeply interfused,” the artist must leave behind “the fretful stir / Unprofitable, and the fever of the world”; he must turn his back on the world and face the vast depths (whether it is a sea of fog or a sea pure and simple) that lie within himself, for all true spiritual understanding emanates from something within us, from the deepest parts of ourselves, which the intellect has not the power to comprehend. This is why, as Northrop Frye tells us, “[a]ny genuinely creative individual is likely to be regarded by society as antisocial or even mad.”

So the artist stands at the edge of the known world, turns his back on it, and must cross—what? See you on the Other Side of what? Between my current position and the place where stands all that I have the power to see—that is, to imagine, to create—likes a vacuum, a void, an infinite emptiness. This void is the blank canvas, the blank page, the as-yet-uncreated, the imagination stultified and overwhelmed and rendered speechless by what it imagines, such that it cannot even put one foot forward to move ahead through the annihilating fog. In the Fellini movie Amarcord (1973), one morning Titta’s grandfather finds himself so steeped in fog that he cannot even tell he is in front of his own house. Is death like this? he wonders. Yet move one step here and a gate emerges, there and a tree. Distance itself engenders desire; to see the endless expanse between here and there can paralyze, but it can also inspire us to take that first step, to walk across the void.

Indeed, art is the attempt to traverse that void, to sail across the sea of fog, to get to the Other Side. How rarely are we granted glimpses of another’s inner life, of another’s private world! Fog shrouds it, distances numb us. The backs of others are turned to us, and what their private griefs are, their secret hopes, the idiosyncrasies of their imaginings, we don’t know, except in rare sublime moments of love or transcendence. “If we could only get round in front—” says Syme in G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday. But some things can only be gotten through the backdoor. I think this is the position from which we humans approach God: his front is unknowable, and yet he is not fully alienated, for we still have his back, from behind which we can peer over his shoulder at the sublimity of creation. With the Rückenfigur, the artist, “God of creation,” extends a hand to you the viewer. Get in the boat, he says, we are going to cross the Sea of Fog.

Anne Carson, “On Walking Backwards,” Plainwater: Essays and Poetry, 1995.

“The artist, like the God of creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails,” from James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Keith Allan, "The Anthropocentricity of the English Word(s) " Back," Cognitive Linguistics 6, no. 1 (1995), 11.

The author of On the Sublime is unknown but generally referred to by the name Longinus.

Northrop Frye, Fables of Identity.

Anne Carson, “Foam (Essay with Rhapsody),” Decreation, 2005, italics mine.

Bringing these two artists together like this is absolute genius, Ramya. And I also love your meditations on Rückenfigur in general - (not to mention the fascinating digression into relativity and ghosts too)

This would make such a brilliant exhibition.

Interesting. Thank you. Can I add Karsh's portrait of Pablo Casals to your meditations. It is perhaps in his top two or three, after Churchill and Hemingway...perhaps. But it is very definitely a portrait. And it is from behind. You may enjoy it.