This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

The Deathless Song of Gatsby

The great mythology of the American Dream has not been captured better before or after Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald laid pen to paper a hundred years ago and dreamed up that sublime, haunting prose romance, one summer and barely 50,000 words long, in which James Gatz of North Dakota, now smoothed, moneyed, polished into “Gatsby,” attempts to recapture his romance with Daisy Buchanan, to disastrous effect. Disastrous only for him, though—that is its tragedy.

Daisy and Tom, guarded by their wealth and their status and their class and the carelessness they can well afford, escape unscathed. Both may have lost their lovers, both may have been shaken up, but life will continue for them the same as ever. They will swan off to summer elsewhere, and the beautiful houses with the beautiful lawns and the beautiful clothes and the beautiful cars and the servants and the footmen and the butlers and the housemaids and the mistresses and the ability to declaim with impunity at the dinner table about “The Rise of the Coloured Empires” and the submerging of “the white race” and “beating them down” will remain, and, whatever the unhappiness in their marriage, they will not leave each other in order to lose all that, toppling down into that class of people, poor things, who actually have to worry about the consequences of their actions.

That is because they have everyone else to mop up the consequences of their actions for them. However great Gatsby grows, he will forever remain this mop. Daisy can accidentally hit her husband’s mistress Myrtle with a car, and Gatsby will take the blame for it, get shot, and collapse into the swimming pool of the mansion that is at once the culmination of his stratospheric ascent and the symbol of his perpetual non-belonging. The best tragedies, the most accurate to life and most tragic tragedies, are always a series of mischances and accidents that are also at one and the same time the inevitable result of the characters of the people involved. This is also what we call fate.

That Tom and Nick and Jordan go off to the city in Gatsby’s “circus wagon,” while Daisy and Gatsby follow in Tom’s coupé, that Gatsby’s car is low on gas and Tom must stop at Wilson’s gas station, whose proprietor, Wilson, is husband of Tom’s mistress Myrtle, that Wilson, surly, jealous, suspicious, intends to take his wife out west, “whether she wants to or not,” while Myrtle peers down from an upstairs window, that it is a hot summer day that distempers everyone, that there is a fight where “tragic arguments” occur and Nick’s 30th birthday is forgotten, that Gatsby and Daisy drive back to Long Island now in Gatsby’s car, and that Gatsby, thinking “it would steady her to drive,” gives a “very nervous” Daisy the wheel, that Myrtle Wilson, remembering the car and Tom in it from earlier, unleashes her store of “tremendous vitality” to run out onto the road, be killed, and set her husband off with a warm gun on a quest for revenge—how could any of it have been prevented, untangled, intercepted? The Fates within us sit and spin, we provide the fiber, and everything unfurls as it must.

All learning is imitation, and a few years ago I conducted an experiment in which I retyped the whole of The Great Gatsby. I was struck most of all by its length—somehow in my mind it had been two or three times longer, having loomed in my imagination with such epic grandeur—and by its absolute concision. Perfection is when nothing need be added, nothing taken away, and as far as it is possible for any human work to achieve perfection, Gatsby was one of those rare, gemlike creations, compressed and luminous and whole, glittering out immaculately the care of its cut and polish. Usually when we get beautiful prose, it luxuriates in itself, spreads out like diaphanous chiffon, evaporates in a kind of formlessness that we forgive because of its beauty. But the beauty of Gatsby is contained, well-ordered, necessary. Words are chosen for their accuracy, for after all, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

Under this Keatsian principle, plot, character, prose beauty, symbol and image—all unite under truth’s banner and, sonnet-like, we get the feeling that Fitzgerald has labored to “weigh the stress / Of every chord” in order to fit the novel with “sandals more interwoven and complete.” It was in Fitzgerald’s 1920s that novelists like Woolf and Joyce were throwing off the corset of plot to stretch out prose’s muscles into poetry, but in Gatsby Fitzgerald knew, like Shakespeare, that plot is poetry, and that events can signify, reverberate, and peal out beyond themselves. Myth is created, codified, and perpetuated by literature, and the American mythos was still missing its bard.

We may not have Zeus and Hera, we may not have selkies and rusalki and fairies, but we have the American Dream, which has not faded or changed much in a hundred years. It is the belief that whatever your background, wherever you came from, whoever you are, in the Land of Opportunity all things are possible. All the accidents of birth and circumstance can be transcended. If you have some genius or brains or personality or beauty and the determination to succeed at all costs, you can gain splendor, wealth, success, and therefore happiness. The Baz Lurhmann adaptation of Gatsby features Lana del Rey’s “National Anthem,” which croons, “Money is the anthem of success.” Daisy’s voice is “full of money,” the green light is green like the glow of the greenback, but it is not exactly money that Gatsby is after, nor Daisy, nor love, nor the parties and the mansions and the achingly beautiful shirts, but something over and above it, something “beyond everything,” large as only myth is large.

Daisy’s maiden name is “Fay,” after all, as in fairy, and Gatsby wants “a promise that the rock of the world was founded securely on a fairy’s wing.” The dream may be delusion, but there is always something innocent, pure, incurably honest in a dreamer. “You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together,” Nick tells Gatsby. Without the dream, this country of pioneers pushing relentlessly west and scrambling over one another and enslaving and killing and hunting and selling and buying and panning for gold and trading on the stock market and erecting mansions and destroying nature and native peoples would be something dirty, sordid, contemptible and wretched. But a dream is always beautiful, a dream gleams, flowers, sustains: “for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent… face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

The dream outlives the dreamer, never mind that the dreamer fails or dies. We are still haunted by this story as Gatsby is by the green light and Daisy’s nightingale voice, as the valley of ashes is by the godlike gaze of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg. “Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!” The hungry generations await thee eagerly, listening for the cool vintage of your song, ready to fly with you “on the viewless wings of Poesy.”

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Old Westbury Gardens in Long Island, New York: In The Great Gatsby, the old money aristocracy, like Tom and Daisy, inhabit Long Island’s (fictional) East Egg, while the nouveau riche like Gatsby must make do with the West Egg. This house, built by John Shaffer Phipps (his father, Henry Phipps, Jr., was friend and neighbor to Andrew Carnegie and co-founded Carnegie Steel) as a wedding present for his fiancée Margarita Grace, was meant to recreate for her the English country house feeling she’d grown used to in her native Britain. It later served as the inspiration for Tom and Daisy’s estate in Baz Lurhmann’s 2013 Gatsby adaptation.

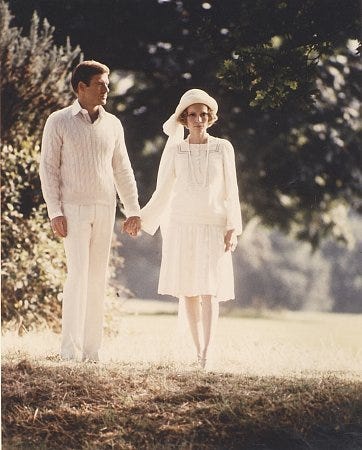

Wedding portrait of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre: Zelda was not Fitzgerald’s first love, but she was the girl he married, in 1920. Mirroring Jay Gatsby’s meeting of Daisy, the young Fitzgerald met the teenage Zelda when he was stationed outside of Montgomery, Alabama, while enlisted in the army during WWI. Zelda’s family was wealthy and had a prominent Confederate past, while Fitzgerald’s uniform hid his lack of affluence—though not for long. Zelda refused to marry Fitzgerald unless he could support her; he despaired, prevailed, published his debut, The Beautiful and the Damned, and he and Zelda soon wed. So eager was Fitzgerald to marry her that he had the priest commence the solemnities even before all 10 guests at St. Patrick’s Cathedral had shown up!

“La danseuse aux jets d’eau” illustration by George Barbier for Gazette du Bon Ton (1924-25): Art deco, the Flapper, the magazine boom, the still nascent and expensive state of photography—all resulted in the 1920s being the prime of fashion illustration. Magazines made the illustrators, and illustrators made the magazines—one such fruitful match was that between the French Gazette du Bon Ton (1912–1925), founded by Lucien Vogel, and illustrator George Barbier, whose work infused the creations of the great fashion houses with romance, whimsy, poetry and pathos.

Mia Farrow as Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby (1974): The 1974 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, starring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, is a bit lackluster compared to Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation, starring Leonardo diCaprio and Carey Mulligan, but I just adore this ensemble that Farrow’s Daisy wears at a party: the shimmering pale blue dress with its handkerchief hem, the glittering cap, the long strand of pearls and champagne coupe as accessories.

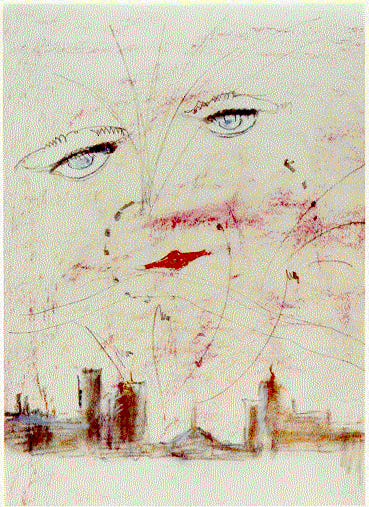

Costume designer Theoni V. Aldredge won an Academy Award for Best Costume Design for this 1974 adaptation of The Great Gatsby Francis Cugat’s painting for the cover of “The Great Gatsby”: This has to be the most iconic book cover in publishing history. The deep blue, the luminous eyes that send out their disembodied gaze over the whirling colorful carnival of the city, the rosebud lips. The obvious inspiration is “the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleberg… blue and gigantic,” but the femininity of the features can’t help but remind me of Daisy, a lost phantom of the past, forever haunting Gatsby’s big city aspirations.

Cover of the February 4, 1922 edition of The Saturday Evening Post: Fitzgerald’s short stories were published in The Saturday Evening Post several times, bringing him to an audience of about two million. The cover features the Flapper, whom I can never think about without remembering Zelda Fitzgerald’s unflappable prose: “the Flapper awoke from her lethargy of sub-deb-ism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge, and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt… and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring. She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do. Mothers disapproved of their sons taking the Flapper to dances, to teas, to swim, and most of all to heart.”

some other magazines Fitzgerald published stories in “Where there’s smoke there’s fire” illustration by Russell Patterson (1920): I love the magazine illustrations of the 1920s—their precision, their flair, their freshness, their fashion, their art deco delicacy. Patterson (1893–1977) captured and created the Jazz Age woman through his numerous illustrations for the big magazines of the day, ushering in the era of the Flapper, and I was reminded of this passage in Gatsby where, looking at Jordan Baker, Nick observes: “She was dressed to play golf, and I remember thinking she looked like a good illustration, her chin raised a little jauntily, her hair the colour of an autumn leaf, her face the same brown tint as the fingerless glove on her knee.”

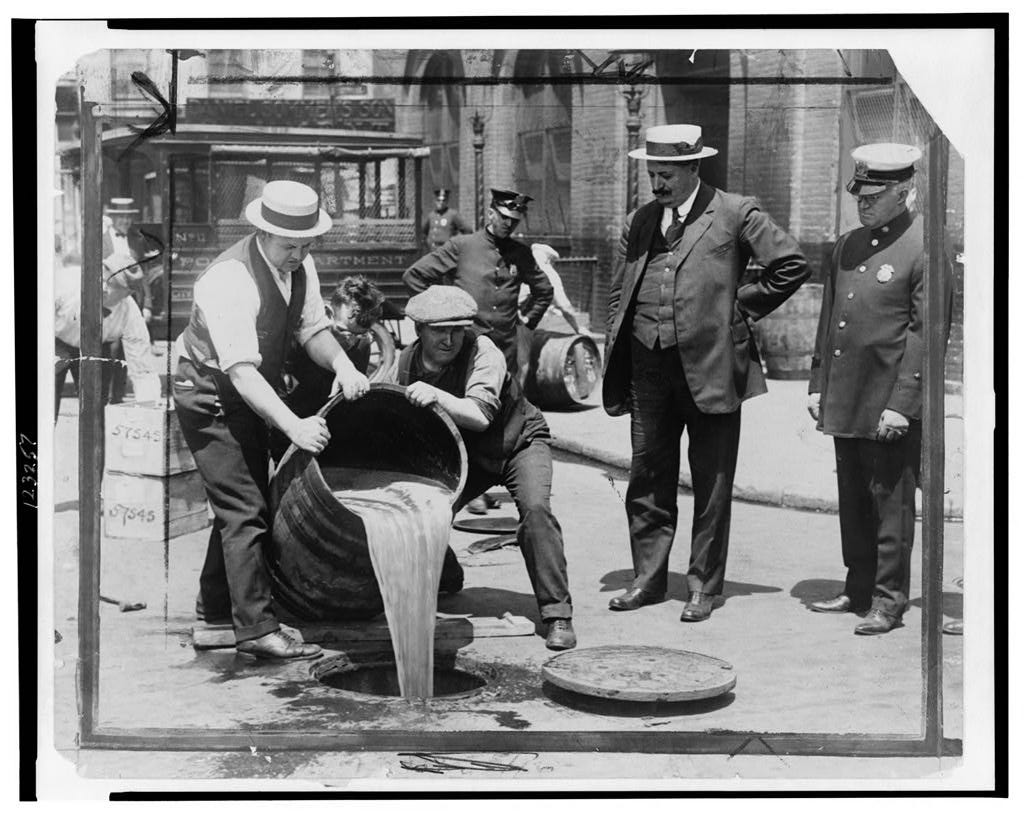

“U.S. IS VOTED DRY” headline for The American Issue, January 16, 1919: After decades of campaigning by religious reformers, physicians, and women, the temperance movement swelled to a crescendo in the early 20th century, culminating in the ratification of the 18th amendment in 1919, which prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” But the forbidden fruit tastes sweetest, and Prohibition only led to the proliferation of speakeasies and bootlegging, which in turn spurred the rise of organized crime. This is, in fact, how Gatsby got his gold: “He and this Wolfshiem bought up a lot of side-street drug stores here and in Chicago and sold grain alcohol over the counter.”

Bessie Smith, photographed ca. 1925: The “Empress of the Blues,” Bessie Smith was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, either 1892 or 1894. By the time she was nine years old, both of her parents had died, leaving Bessie and her six siblings to fend for themselves. Attempting to dig themselves out of poverty, they busked on street corners, and there’s nothing like having to sing for your supper to make you polish those pipes. By 1913, she struck out on her own, building her reputation as she performed in theaters and venues across the South, resulting in a record deal with Columbia Records in 1923. Her powerful contralto, her frank treatment of the everyday realities of poverty, racism, and heartbreak, and her formidable stage presence (at a height of over six feet and a weight of over 200 pounds) soon made her the highest-paid African-American in the music industry. Her career was cut short by her death by car crash in 1937, and though thousands turned out for her wake, it wasn’t until 1970 that this queen of the Jazz Age got a tombstone, courtesy of her former housekeeper Juanita Green and Janis Joplin.

3 Things Gatsby Quotes I’m in Love With This Week:

“In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars.”

“Anyhow, he gives large parties…. And I like large parties. They’re so intimate. At small parties there isn’t any privacy.”—this is Jordan Baker speaking to Nick at Gatsby’s party, being very relatable.

“On buffet tables, garnished with glistening hors-d’oeuvre, spiced baked hams crowded against salads of harlequin designs and pastry pigs and turkeys bewitched to a dark gold.”—I just love that description, “turkeys bewitched to a dark gold.”

Words of Wisdom

In 1933, Fitzgerald sent a letter to his eleven-year-old daughter Frances (“Scottie”) while she was away at summer camp, imparting many words of fatherly wisdom. In the letter are two lists of “Things to worry about” and “Things to not worry about.” The questions he poses as “Things to think about” apply whether you’re eleven or eleventy-one, and one wonders if Fitzgerald didn’t intend them for his own use as well.

Things to worry about:

Worry about courage

Worry about cleanliness

Worry about efficiency

Worry about horsemanship...

Things not to worry about:

Don't worry about popular opinion

Don't worry about dolls

Don't worry about the past

Don't worry about the future

Don't worry about growing up

Don't worry about anybody getting ahead of you

Don't worry about triumph

Don't worry about failure unless it comes through your own fault

Don't worry about mosquitoes

Don't worry about flies

Don't worry about insects in general

Don't worry about parents

Don't worry about boys

Don't worry about disappointments

Don't worry about pleasures

Don't worry about satisfactions

Things to think about:

What am I really aiming at?

How good am I really in comparison to my contemporaries in regard to:

(a) Scholarship

(b) Do I really understand about people and am I able to get along with them?

(c) Am I trying to make my body a useful instrument or am I neglecting it?

Poetry Corner

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare; Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss, Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve; She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

—John Keats, from “Ode on a Grecian Urn”

Harold Bloom points out the influence of Keats’ “Eve of St. Agnes” on Fitzgerald, John Pistelli in The Metropolitan Review describes Fitzgerald’s metamorphosis of Romantic poetry into the novel form, and George Monaghan in that same journal writes of how Gatsby is haunted by the Keatsian nightingale.

But Gatsby’s story always reminds me of the “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” and I am sure that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty” is his secret credo. On that urn the figures are perpetually, immortally stuck in their poses and attitudes, the trees are forever lush and green with springtime leaves, the heifer is forever “lowing at the skies,” the fair youth is forever piping his “spirit ditties,” the fair maiden is forever unkissed but just within grasp. Everything is paused in its potentiality, like money in the bank, unspent and therefore able to buy anything and everything.

Ostensibly, Gatsby wants Daisy, he wants the American Dream, he wants money, he wants acceptance into the upper class, he wants beautiful silk shirts, he wants the green light at the end of the dock across the bay, but what he wants above all wants, without being aware of it, is to keep wanting. For Gatsby is a dreamer, and the most painful thing of all for a dreamer is to lose his dreams. For him, the unheard melodies within his head are far sweeter, the unrealized visions far grander, the “still unravish’d” Daisy far more beautiful. But nothing can live up to that, and therefore Gatsby must die, die before he grows old and hoar and gray, die before Prohibition ends and the going gets rough and his criminal entanglements catch up with him, die before he, “bold lover,” wins near the girl and she turns around and rejects him and fades, die before the spring leaves rust and brown, wither and crumple and fall, die before the pipes “leave melodizing” and the heard melodies die out and the song stops. As it is, we remember him “For ever panting, and for ever young,” and the song goes on.

Beauty Tip

Host a 1920s-esque bash and add a Romantic touch from Gatsby—“the beads and chiffon of an evening-dress tangled among dying orchids,” a green light, mysterious looming eyes.

Lingering Question

How far are you willing to go for an “incorruptible dream”?

Dear Readers, I hope you enjoyed this post! If you did, please give this post a like, share with a friend, and subscribe to Soul-Making for more!

If you want a little more reading about The Great Gatsby, I really liked Emma B Heath’s post in The Metropolitan Review about teaching this American classic, as well as Naomi Kanakia’s reflection on close-reading it!

Thanks Ramya for the mention in such a rich and interesting letter :)

My slightly jejune inclusion of Keats in that essay has brought me lots of pointers on where to go next, including one commenter who literally wrote the book on Keats and Gatsby lol.

I think your bit from 'Ostensibly' to 'more beautiful' is bang on and very nicely phrased. Thanks again and hope you have a nice weekend,

GM